Forum

Pics or it DID happen: Are we finally recognizing the frivolity of content creation?

Illustration by Erica Shi

Earlier this year, when asked what it was like to go out before social media, actress turned business mogul Gwyneth Paltrow reflected on nightlife in the nineties. She responded,

“It was great — I mean talk about doing cocaine and not getting caught! Like, you could just be at a bar and be, like, having fun, dance on a table…You could stumble out of a bar and go home with some rando and no one would know.”

This romanticized (even in Paltrow’s LA-speak) ideal of freedom and rebellion before the modern surveillance of the cell phone is forcing a distinction between creating content and having human experiences.

The notion of “pics or it didn’t happen” is more than just an adage that high school girls use for their Instagram bios. Around the same time Instagram became a beacon for content-creation, designing businesses, events, and activities with the specific intention of having them go viral became the norm. Crafting perfectly-curated Pinterest boards for an event wasn’t enough; you had to make sure the event would become Instagram-worthy in its own right. It became common knowledge to restaurants, bars, and clubs that the way to bring in guests was to have a photo wall, an incredibly photogenic interior, or some kind of gimmick that was sure to go viral. As consumers, we used to think that social media content was equivalent to a good time, but recently, those things have started to become mutually exclusive.

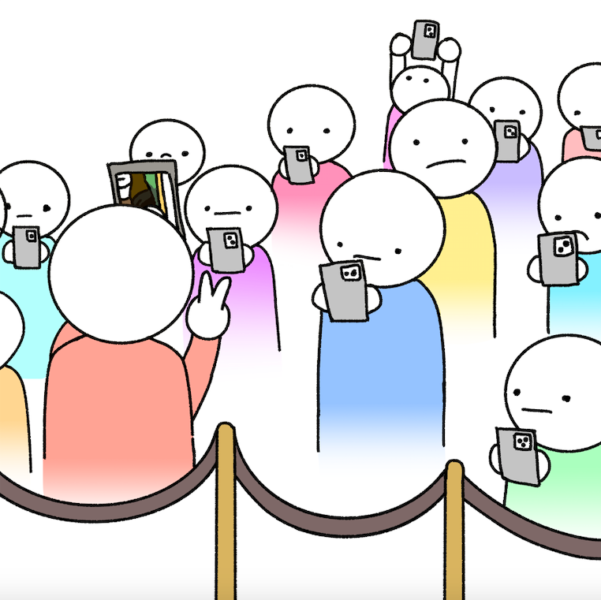

While there were many reasons for their decisions to institute no photo policies, museums were some of the first institutions to recognize that photography inside worsens the customer experience. Many museums and cultural institutions around the world, like the Sistine Chapel, Monticello, and special exhibits at the Van Gogh Museum don’t allow photography. We’ve all seen photos from inside the Louvre, which houses the Mona Lisa, where the portrait is flooded not with interested viewers, but with cell phones.

If social media represents inclusivity, the lack of it represents exclusivity. Berghain, one of the most famous clubs in the world located in Berlin, recently gained lots of traction on TikTok for its incredibly strict door policy, but it has been suggested that what really gives Berghain its hyper-cool image is its strict no photo policy. It’s not just inside the club that photos are frowned upon. Bouncers are notorious for turning guests away at the door if they were even on their phones in the line. When you choose who to admit based on “vibes,” having a phone glued to your hand is a surefire way to lose cool points. Fabric, a popular EDM club in London, has the same rule.

One of the reasons that photo-free experiences are becoming more coveted is the lack of constant surveillance that they foster. Cancel culture has solidified the notion that a photo can ruin your life, and the chances of having an eyewitness to any kind of bad behavior have skyrocketed as photos are shared constantly across platforms. There is no need for an Orwellian Big Brother when we are governing ourselves through the media we create and consume. Having photo documentation of your entire life is terrifying, at least to me, and most of those images will never go away. This is especially true for celebrities, influencers, and other media personalities, especially those who became famous at an early age.

A few years ago, it seemed to me that there was nothing cooler than being an influencer, except the idea that it could happen to anyone. Emma Chamberlain went from making Youtube videos in her bedroom and at her high school to walking the Met Gala red carpet. TikTok has increased the number of influencer success stories exponentially, launching Internet mega-stars like Charli D’Amelio, Olivia Dunne, and Alix Earle.

But with the rise of more and more Internet sensations came a new online trend: Deinfluencing. While influencers tout the benefits of their sponsored products and encourage you to invest in the latest trend, deinfluencers convince you NOT to buy the Dyson Airwrap that Alix Earle used in her latest Get Ready With Me nor the Marc Jacobs Tote Bag from Kendall Jenner’s advertising campaign. This represents a more general consensus forming about disingenuousness and media, which is being reflected in the things we find cool, like clubs without photos, experiences you can only have with your own eyes, and deinfluencing.

In her book “On Photography,” Susan Sontag writes, “To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge -– and, therefore, like power.” Through photography and social media, we have the ability to show others the world as we see it. We have the power to manipulate the events, people, and behaviors going on around us, and, in turn, our own actions, behaviors, and choices can be manipulated by others.

Now, I’m not saying we should all fly to Berlin and live out Gwyneth Paltrow’s wildest club fantasies, but I am excited about a push towards living in the moment rather than through our screens, and I think we should do our best to perpetuate that shift.