Scene

A unique opportunity: Wash. U.’s rare book collection

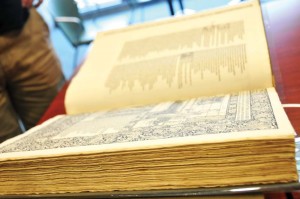

A page from “The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer,” reprinted in the 1890’s. The book is part of the Triple Crown Collection, acquired by Olin Library in 2000, which includes all published outputs of presses representing English Arts & Crafts bookmaking.

“The question we always get is ‘Can we really touch that?’” said Anne Poesga, head of the Department of Special Collections at Olin Library.

Despite the rarity and age of many of the books kept in the humidity-controlled storage vault in Olin Library’s special collection, visitors are in fact encouraged to gently read and interact with the books. But in a world where such information exists online or in modern publications, interest has shifted away from the words and towards the construction and printing of the books.

“A lot of [the value] is context. I think when you see how much work went into making an older book in particular you realize how it was not necessarily common for everybody to have a big library, and how books were a much more rare commodity than they are now,” Posega said.

About half of the classes that visit the department come from the history, literature and classics departments. What fewer people may suspect is that is that the most heavy users of the collection are art students, Posega said. The Rare Books Collection aims to give students a respect for the way a book’s form meets it’s function in the art of making books by hand before mass-production. This respect is a tradition that dates back centuries, one which the Rare

Books Collection documents through its expanding inventory.

One major goal of the Rare Books Collection is to expand what it calls its “Triple Crown” collection—books from three turn-of-the-century publishers involved with the English arts and crafts movement. This movement, which focused on bringing back a more artful approach to book making, is best represented by The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, printed in 1896 by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press.

“[Morris] felt that he lost a lot when things weren’t handmade,” Posega said. Morris’s concerns are even more relevant today as books grow more disposable or, in some cases, nonexistent. To see his work in person, observe the intricacies, and practically feel the blood, sweat, and tears on the paper is a perfect reminder of how the medium can be just as important and beautiful as the words printed on it.

One of the most common requests in Olin’s Department of Special Collections is a set of books taken from Thomas Jefferson’s personal library. Though the library acquired the books in the 1880s, they were not identified as Jefferson’s until two years ago. The collection is the third largest in the country, and it offers anyone, student or otherwise, the opportunity to come as close as any living human can to shaking our third president’s hand.

However, when your hand is hovering inches above a priceless book written by someone your great-great-grandfather would have considered ancient, it’s a little intimidating, even knowing you’re allowed to touch.

“You don’t want to lean on Jefferson’s book,” Posega laughed.