News

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Olin students to receive notification letters explaining University’s compliance at career fairs with military’s LGBT policies

Senior David Dresner, co-founder of the “Right Side of History.” (Sam Guzik | Student Life)

Pat Carr | MCT Campus

Several weeks ago, senior David Dresner approached a military recruitment table at a University career fair, announced that he was gay and asked for an application. He was promptly denied.

The moment was not an extraordinary one.

Campus career fairs contradict the University’s non-discrimination policy by allowing the United States military, which will not enlist openly gay men and women, to recruit on campus. The University career fairs generally host employers that have non-discriminatory hiring policies akin to those of the University’s.

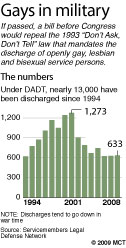

But because the University receives federal funding, it is required by law to allow military recruiters on campus, even though the military’s policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” bars openly gay people from enlisting in the armed forces.

Law students are already aware of the University’s conflicting obligation to allow recruiters on campus, as they are notified by letter every time military representatives attend a law school career fair. Now, thanks to the “Right Side of History” LGBT rights campaign, undergraduate students will soon be receiving similar notifications.

Dresner, co-founder of the “Right Side of History,” is spearheading a movement to bring similar notification letters to all undergraduate students. The “Right Side of History” seeks equality for the LGBT community by engaging straight youth. Dresner recently met with representatives from the Olin Business School, who agreed to send out the letters to business students.

“[They] were incredibly supportive, enthusiastic and gave me ways to move forward,” Dresner, an Olin student, said of the business school representatives.

Mark Brostoff, dean and director of the business school’s Weston Career Center, says he believes the letters will make clear that the University does not support the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

Brostoff, an openly gay man, served in the U.S. navy from 1982-2002, before and after congress implemented “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Since he left the military, Brostoff has been nationally recognized for his work with LGBT career development.

“[The letters are] an acknowledgment that military recruiting on campus is not aligned with our school’s non-discrimination policies and that we recognize this as a matter of law that we do not condone,” Brostoff wrote in an e-mail to Student Life.

Senior Michael Freedman, a member of the “Right Side of History” campaign, says he thinks notification letters will help raise awareness on campus about society’s discrimination against gays and lesbians.

“I think [a letter] sends the message that discrimination is something real and is still happening now,” Freedman said. “I think oftentimes we mistakenly think of discrimination as a thing of the past. Hopefully, the letter will cause some straight students who maybe haven’t thought about the ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy or discrimination against LGBT people to think,” Freedman said.

History: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and military recruiters on campus

News of the notification letters comes just days after President Obama announced that he is committed to ending “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Obama’s pledge, made at a benefit on Saturday for the LGBT rights group Human Rights Campaign (HRC), comes more than 15 years after the military’s policy went into effect.

“Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was enacted under the Clinton administration in 1993. In response, many schools refused to allow military recruiters on their campuses. Congress, in turn, responded with the Solomon Amendment, a 1995 law that permits Congress to cut federal funding from any university that does not allow military recruiters.

“[The Solomon Amendment] was this poison pill that schools were forced to swallow,” said Davin Rosborough, former president of OUTLaw, the law school’s LGBT activist group.

Following the Solomon Amendment, law schools across the country started sending notification letters to their students.

Rosborough says he understands the University is abiding by the Solomon Amendment but emphasizes that the University is not obliged to follow it.

“I think many of us understand the choice that the University made but we should remember it’s still a choice, although the University’s hand was forced,” Rosborough said.

Drafting the letter

Freedman is currently working with the deans of the business school to draft this letter. Set to be sent out before the next business school career fair, the final letter must be approved by Dean of the business school Mahendra Gupta.

The Right Side of History is currently working with Mark Smith, director of the Washington University Career Center, the National Society of Black Engineers and deans from each of the University’s individual schools to get other career fairs on campus to issue similar letters. .

Jim Holobaugh: Openly gay and former WU ROTC cadet

Perry Stein

Editor in Chief

The direct consequences of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” have a history on Wash. U.’s campus. Jim Holobaugh, a 1990 alum and former Army cadet who attended the University on a four-year ROTC scholarship, had his scholarship revoked in 1990 after he came out as gay. Although the Army eventually reversed its decision, this incident brought Wash. U.’s ROTC program to the forefront of the national media in the early ’90s.

Last spring, Wash. U. hosted the inaugural James M. Holobaugh honors—an awards ceremony recognizing leadership and service to the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. The awards ceremony was created to commemorate Holobaugh’s story.

Holobaugh discussed his opinions on the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy while on campus last year for the awards ceremony.

“I think it’s a bad policy,” he said. “I think it should change. I think it will change probably in the not-too-distant future. It’s enforced in a very haphazard way.”