Forum | Staff Columnists

The shapeshifting face of American superheroes: from Marvel to The Boys

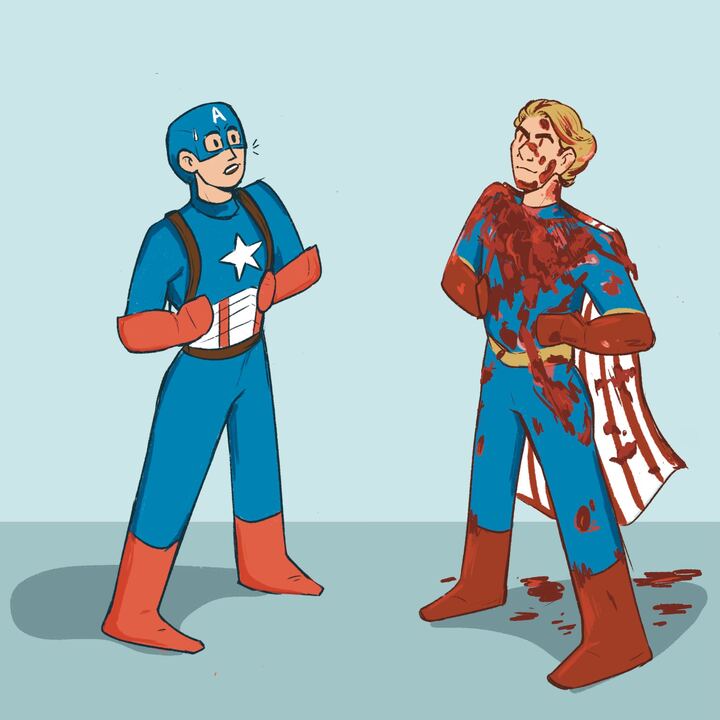

Illustration by Jaime Hebel

Illustration by Jaime Hebel Marvel’s brilliant experiment — creating a series of movies that all take place in the same world — is reaching its breaking point.

There are great shows and movies being released — in my opinion, “Loki” and “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” are among them — but the sheer volume of films and TV shows and spin-offs no longer feels unified. Amid this convoluted expansion, Marvel generally continues to hail superheroes as arbiters of peace, a symbol of proper criminal enforcement.

Marvel may have a strong hold on the industry, and that reign likely isn’t ending anytime soon, but a new generation of American superheroes is assembling.

Shows like “Invincible” and “The Boys” (and its spin-off series, “Gen V”) portray superheroes as nuanced, oftentimes highly problematic characters. These characters show a facade of crime-fighting heroism to the public, while behind the scenes they’re evil, power-thirsty narcissists.

Superheroes have always been a reflection of political and cultural attitudes. The Superman, Batman, and Captain America comics were created in the 1930s and 40s as American war propaganda. Black Panther was born out of the 1960s civil rights movement. Northstar was introduced by Marvel during the 1970s queer activist movement. And Gen V’s very recent Jordan Li adds nonbinary representation to the industry.

However, the recent shift in portrayals not only adds representation to the superhero world but also challenges the notion of superheroes altogether. This change seems reflective of a larger social phenomenon: a widespread distrust of people in power.

In “The Boys,” Homelander — leader of The Seven — is corrupted by glory. If Donald Trump thinks he can walk onto 5th Avenue, shoot someone, and still have supporters, Homelander knows that he can do worse. Homelander can crash an airplane, kill innocent people, overpower civilians, and still rally a crowd of fans waving flags, sporting Homelander t-shirts, and crying chants of “American Safety First.”

In the same vein (and I am keeping this as vague as possible to avoid spoilers), “Invincible” has a Homelander-equivalent. It becomes clear after the first episode that heroes aren’t all they claim to be. Okay, spoiler: They’re a whole lot worse.

Unfortunately, these shows are also a whole lot more accurate to what people with superpowers would probably do to each other — how they’d use that power to stomp out political rivals, cover up their tracks, and distract the public.

“The Boys” has seen record growth in viewership. According to the official X account of the show, “Invincible” has also experienced a continued uptick in watchers and fans. This is happening while the Marvel universe has been finding it harder than ever to cover production costs at the box office (not to mention the DC universe’s financial returns, which — perhaps to little surprise — have been on a steep downward slope, as well).

While “The Boys” and “Invincible” have their fair share of shock-value violence (where it’s pretty easy to tell that the makers had a bit of fun ripping people in half), the intensity of it serves a purpose. Rather than shuddering at the sight of blood, most viewers seem to appreciate the brutal, raw reality being shown.

No more turning a blind eye to the colossal damage made in the wake of every superhero fight. We see it. We see that city you ravaged all just to catch one guy.

Viewers are supporting this unmasking of superheroes, this blurring of hero and villain.

It is no coincidence that this shift is happening during a record-low plunge in government trust. According to the Pew Research Center, fifteen percent of Americans say they trust the government “most of the time.” One percent says “just about always.” In the early 2000s, the average of these figures was closer to fifty percent.

In a time of still-rampant police brutality, resentment toward American global affairs, embarrassing political officials, and an onslaught of other issues, it doesn’t require X-ray vision to see right through the ludicrousness of the American political system and to understand why this decline in trust is happening.

While the falling off of Marvel may seem like the end of superheroes, I can assure you that the genre is not going anywhere. The superhero industry is simply casting aside its Clark Kent glasses, revealing a new, culturally relevant identity.