News

Invisible on campus: The slow progress and campus-wide frustration of recruiting black faculty

Invisible on Campus is an investigative series that takes a multifaceted look at the past, present and future of black oppression on campus. In its first three installments, we looked at the current climate of diversity and inclusion on campus, the history of black student activism at Washington University and efforts to boost black representation through undergraduate admissions. Today, we examine the University’s similar goals and outlook for diversifying its faculty.

Michelle Purdy is in many ways the poster child for how a bright student can trace a path through academia. Coming to Washington University as an Ervin Scholar from Jackson, Miss., Purdy threw herself into extracurriculars once she arrived on campus. She played a part in writing the 1998 Action Proposal as a freshman, served as a resident advisor, interned at the admissions office and became one of the first black women to serve as Student Union president.

As a black student at the turn of the century, Purdy observed the same kind of racially charged divisiveness that current students see at Wash. U. “Were the issues present? Yes,” Purdy said. “Did [students] talk to us about which professors they thought were more respectful to black students? Yes. Did we notice how black workers were treated on this campus? Yes. Did we want more financial aid for black students? Yes. Did we want more black students, period? But Purdy also had a “buffer zone” through the Association of Black Students and the Ervin program, and the longtime Wash. U. community member joked that nobody loves the school more than she does. It’s not a perfect place, she said, but it’s one she’s invested in seeing improve.

In the classroom, Purdy studied education and African and African-American Studies (AFAS), and she stayed at Wash. U. an additional two years to earn her master’s degree in history. Purdy left St. Louis for her Ph.D. coursework and taught at Michigan State University for two years before returning to the Danforth Campus as a tenure-track professor in education—precisely the pattern administrators suggest is the best way for Wash. U. to both educate and recruit talented faculty.

Purdy’s name carries weight—one Wash. U. alumna spoke with Student Life for this story only after learning that Purdy had referred her—and her professors remember her fondly. Rafia Zafar, an English professor who chaired the AFAS program from 1999-2003, can still recite Purdy’s research paper topic for her class from 15 years ago and said she enjoys working with her former student.

“I have to get her stop calling me Dr. Z,” Zafar said. “I say, ‘You’re my colleague now; you have to call me by my name.’”

Purdy is active in recruiting high schoolers to Wash. U. and maintains a close relationship with the Ervin program. Just as when she was an undergraduate, she’s involved with the University community in a multitude of ways, and Zafar and others said that bringing her back to the Danforth Campus was a coup.

It’s also representative of a goal that has been at the center of Wash. U.’s stated mission for the last two decades. In his initial address to the University community in 1995, newly inaugurated Chancellor Mark Wrighton spoke about the need to “attract and retain women and members of underrepresented minority groups” at the faculty level.

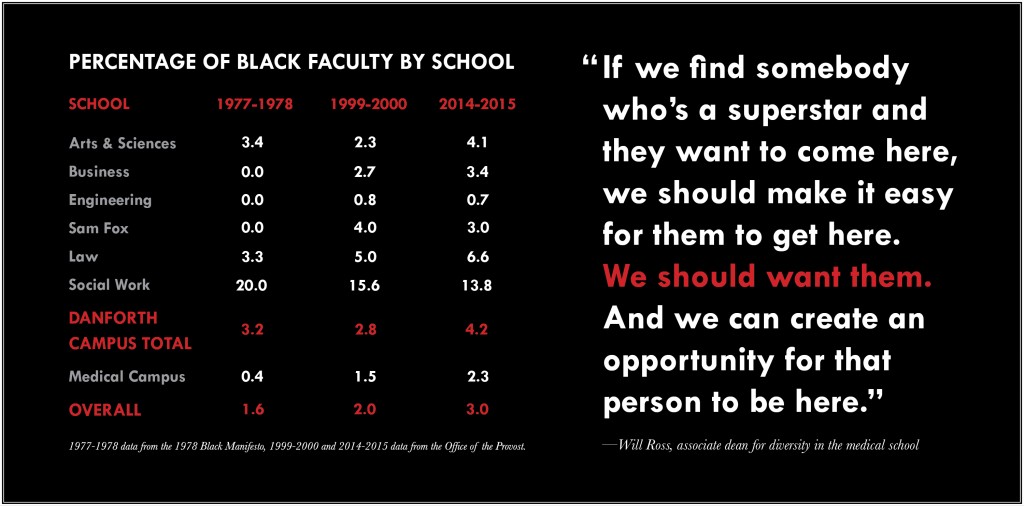

Although Wrighton, who is white, said in a recent interview “it’s not as if no progress” has been made since then, other administrators said that progress has been marginal and painstakingly slow. As recently as last year, you could count on your fingers the number of full time black faculty in the business, art and architecture, engineering and law schools combined.

Wash. U. boasts a number of black administrators, but that diversity hasn’t extended to the faculty ranks, and University officials pointed to these numbers as the hardest to change. Most administrators who spoke for this story had few, if any, prospective solutions for improvement in this area, and more promising ideas and theories from those tasked specifically with diversity work clash with the relative frustration and complacency that exists elsewhere within the University hierarchy.

The progress that has been made has come too slowly, administrators and faculty said, adding that the University needs to adopt a more comprehensive set of programs and efforts aimed at diversifying the Wash. U. professorate if officials are serious about initiating change.

* * *

School deans don’t expect those numbers to budge much in the near future. They were generally They were generally pessimistic about their short-term prospects for improving faculty diversity, with those leaders either admitting they had few ideas to make that fix or acknowledging their doubts about the efficacy of current efforts.

“I think we have to do better. That’s my outlook,” Carmon Colangelo, dean of the Sam Fox School, said. “As an institution, it’s something that everyone’s got to work that much harder at.”

Colangelo, who is white, has been the head of the art and architecture schools since their fusion under the Sam Fox umbrella in 2006. Ever since he’s been here, Colangelo said, Wash. U. has been committed to increasing the diversity of its faculty, but “we’re not having the success that we should…As a school, we have to do better. I’m not proud of our record at all.”

Under Colangelo’s direction, that record is marked by a kind of substandard consistency: each year from 2006 through last year, Sam Fox tallied just two full time black faculty, out of a population generally ranging in the 60s. Colangelo said he’s in the process of brainstorming new faculty recruitment ideas, such as planning better to identify a potential pool of diverse candidates at least a year in advance of a search.

But these efforts are still in their infancy, and for now, Colangelo remains frustrated with the numbers. “We’ve got a long way to go on every front,” he said.

The air of frustration extends from the art school across the front of campus to the engineering complex, where these problems are even more pronounced: The School of Engineering & Applied Science’s faculty counts just one black professor among its 88 full time instructors.

This issue hits the science, technology, math and engineering fields hardest. Similar to the numbers in engineering, only one full time black professor teaches in the natural sciences in the College of Arts & Sciences, according to data provided by that college.

“In computer science, if you have a master’s degree, you’re making six figures the day you walk out the door. These days, actually, with a bachelor’s degree, you’re often doing that if you come from a top school,” Bobick said.

The national numbers bear out Bobick’s concerns. In a 2014 report, the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering calculated that black engineers comprise just 2.5 percent of total engineering faculty across the country. For Wash. U., that number means adding just one black professor would bring the engineering school close to the national average; adding two would boost Wash. U. past the mean.

But in Bobick’s telling, widening the pipeline of prospective professors “takes forever,” and, in the meantime, the University can’t improve by meaningful amounts without a larger cultural shift. “It’s pretty hard for a single person in a university to effect that change,” he said of his role in the process.

* * *

Bobick’s reference to the professorial pipeline was instructive. The term “pipeline” appeared in a number of interviews for this story, becoming an explanation and a justification wrapped up in one convenient buzzword. There aren’t enough black Ph.D. candidates, a source began, before explaining what’s wrong with the pipeline: it’s a problem not just for Wash. U. but for higher education as a whole, we need to widen the pipeline, we need to find out where our pipeline dries up and so on.

The pipeline—or step-by-step process by which potential professors travel from undergraduate student to tenure-track teaching—leaks, administrators explained, because of a variety of factors that plague higher education. Simply, pursuing a career in academia means staying in school longer to make less money, and that’s not a trade-off many bright young minds want to make. Both the temporal and financial considerations can be a deterrent.

The rhetoric from contemporary administrators is similar to that of University officials from decades ago. In a 1978 Student Life article on the absence of any black faculty in many of the University’s schools and departments, Leon Gottfried, then the dean of the faculty of Arts & Sciences, attributed recruitment problems to a limited applicant pool.

“Gottfried said that there are currently very few blacks in graduate programs in the natural sciences and engineering; thus there are very few candidates for teaching positions in these areas,” the article reported.

Four decades later, University administrators were reluctant to ascribe blame for the continued pipeline problems to Wash. U. itself, but rather they shifted the discussion to the failures of higher education as a whole. Nationally, around 5-6 percent of full-time collegiate faculty are black, compared to just over 4 percent at Wash. U. (not counting the medical school).

“Higher education hasn’t done our job by allowing this problem to occur,” Provost Holden Thorp, who is white, said. “You can’t blame any one school for it, but it’s something that everybody has to own.”

Wrighton voiced a more pointed concern, crediting Wash. U.’s progress at the same time that he decried how “academia” as an institution impedes the expansion of that progress.

A similar sentiment permeated many of the interviews conducted for this story, yielding the collective perception that some administrators, while frustrated by Wash. U.’s low numbers of black faculty, are satisfied with the status quo as long as the University remains in line with its peer institutions.

That’s a problem some top-level executives have noticed from their colleagues, too, which positions a behind-the-scenes debate over the University’s role in effecting change.

Will Ross, the associate dean for diversity in the medical school, thinks attributing blame to the system rather than to the individual university has stifled progress at Wash. U. It’s a notion he said he’s heard a lot in his 19 years here, and only recently has the University begun to consider its own shortcomings and make diversity an institutional priority.

“Sure, we want these things to have happened 10, 20 years ago,” Ross, who is black, said, but “you push and push, and the wall gives a little bit. It took some time to push the wall.”

More cynically, Ross acknowledged, his administrative peers may have been swayed by the demands of external regulatory agencies in ceding to that push.

“We realize that as an institution, we have to present ourselves for licensing and for accreditation, and part of that means we have to document that we really are sincere and we are committed to doing this, not just committing policies on paper, but actually having practices of documented benefit,” Ross said.

* * *

In the school’s favor, Ross said, is that there are proven strategies that work to boost faculty diversity. All that needs to happen is for those efforts to be expanded.

One such practice is target-of-opportunity hiring, which allows a school to hire interested faculty candidates without a specifically planned search for their positions.

“If we find somebody who’s a superstar and they want to come here, we should make it easy for them to get here. We should want them. And we can create an opportunity for that person to be here,” Ross summarized. “If a Nobel laureate decided…I want to go to Washington University, don’t you think we would make an opportunity for that person?”

Over the last five years, 26 of 32 target-of-opportunity hires on the Danforth Campus were for members of underrepresented minority groups, and more than 50 percent of those hired instructors were black, according to internal numbers provided by vice provost Adrienne Davis.

Davis, who is black, also noted cluster hiring as a practice proven to increase excitement around diverse hires. With cluster hiring, different schools and departments agree to hire a certain number of faculty all around a targeted area of research; for instance, Davis offered, the law school, social work school and Arts & Sciences could combine to recruit five new faculty who study immigration.

Davis is a particularly powerful voice directing the University’s push for further faculty diversity. Arriving at Wash. U. in 2008, Davis was the first black woman to receive an endowed professorship in the law school; she joined the provost’s office in 2010 to fill a hole noticed by Thorp’s predecessor as provost, Ed Macias.

Prior to Davis’ appointment, the administration saw diversity as a priority but didn’t give it the comprehensive attention it needed to receive real, tangible gains, Macias, who is white, said. Without high-ranking officials directly in charge of the University’s diversity initiatives, things had a tendency to slip through the cracks and expose the contradiction between the school’s stated aims and its actual efforts.

So the then-provost hired Davis as the vice provost in charge of diversity—a necessary position he had learned from his tours of schools and companies that had made noteworthy strides toward increased diversity.

“The most important thing is somebody has to be responsible,” Macias said. “You make diversity somebody’s responsibility; you don’t just say it’s a nice thing.”

In interviews for this story, Davis’ work was praised at length by other University community members, who referred to her as, among other lofty descriptions, inspirational and particularly adept at turning theory into practice.

Much of that praise came from black students and professors, exemplifying a trend of black administrators in prominent positions having an inspiring effect on more junior community members. The trend reaches from Davis to Lori White—who Wrighton called “probably the best student affairs leader in the U.S.”—to the late Dean James McLeod, whose “every student known by name and story” motto spread across the Danforth Campus.

McLeod was a particularly motivating figure for Michelle Purdy, who marveled at a University leader who could “be this amazing man and be a black man from the south. For me, that really resonated.” Fifteen years later, as a faculty member herself, Purdy offered similar praise for Adrienne Davis, whose work in diversity she commended as encouraging to witness.

And with Davis leading the way, the University has made incremental strides in diversifying its faculty, most notably boosting the raw number of black tenured professors on the Danforth Campus from 22 to 37—although overall faculty increases over that time diminish the percentage increase that that jump signifies.

The vice provost exudes optimism and confidence that the University can achieve its goals. When asked for tangible plans to accelerate the halting progress, Davis spoke without pause for nearly half an hour, offering a wide range of possible solutions that, when taken together as a cohesive, directed unit, she believes can bring Wash. U. up to—and beyond—the national average.

* * *

Beyond Davis and Ross, though, administrators had few concrete ideas to increase diversity among Wash. U.’s faculty. A disconnect appears between those who work predominantly on crafting diversity initiatives and those in charge of actually implementing those proposals. Despite annual workshops for the chairs of search committees, the message of what works isn’t getting passed on to the search parties and hiring chairs.

Communication troubles extend to otherwise optimistic trends in faculty hiring, as well.

In Davis’ view, the University’s first few years of concerted effort in diversity work “refuted some of our own institutional anxieties” about hiring diverse faculty. In order, Davis said, department heads were worried that first, they wouldn’t be able to find qualified minority candidates; second, that hiring committees wouldn’t extend job offers to those candidates; and third, that those candidates wouldn’t accept their offers.

“We have this deeply internalized inferiority about who we are and especially about St. Louis,” Davis explained. “And we thought, oh my gosh, talented minorities, they can go anywhere…no one ever wants to come here.”

The data struck down all those anxieties. In particular, from 2009 through the 2013–14 academic year, underrepresented minority candidates accepted job offers at a higher rate than non-underrepresented-minority candidates in five of the six schools on the Danforth Campus (law being the lone exception).

But that good news hasn’t made its way to the school deans. Multiple school leaders spoke about not being able to find qualified minority faculty in searches or about accepted minority candidates declining job offers at a worrisome rate. In the provost’s office, Davis knows strategies that work and can confidently cite tangible statistics about recent efforts, but the University employees in charge of making actual hiring decisions are acting under flawed assumptions and outdated insecurities.

Administrators also lamented a sort of catch-22 found in higher education, particularly STEM fields: the biggest obstacle to becoming more diverse is not already being diverse because black students interested in a career in academia will be less likely to pursue that path if they don’t see existing faculty who look like and can identify with them.

“We want students to form relationships with all faculty, disregard of color,” Rudolph Clay, the black head of diversity initiatives and outreach services for Wash. U. Libraries, said. “But there are going to be faculty that may have had similar experiences as students…and that are going to be able to form relationships with and that will be able to mentor them in ways because culturally they’ve experienced some of the same things.”

While many Wash. U. leaders echoed this sentiment, Lori White, vice chancellor for students, resisted its allure as an excuse for stagnation in the numbers. For White, having a role model who looks like you is an “extra plus-factor,” but it should be paramount for all faculty to mentor and encourage students to pursue a Ph.D. For instance, White said, her sister became a geology professor at San Francisco State University despite never having had a black mentor in her field as a student.

Shedding the catch-22 mentality is also a matter of practicality, White added, because of the current dearth of black faculty.

“We’re never going to have enough minority faculty to mentor all the minority students, so that means all of our faculty have to be able to mentor people who don’t look like them,” she said.

And that mindset is necessary, White thinks, for Wash. U. to effect real change, not just on the school level but for higher education as a whole.

“Unless we can grow the pool, all we’re going to do is we’re going to steal somebody from Stanford, Harvard’s going to steal somebody from us, Emory’s going to steal someone from [Southern Methodist University], and there’s no net gain to the number of diverse faculty members in the system,” White said.

* * *

There exist a number of programs and initiatives set up to entice both black faculty to come to Wash. U. and departments to hire them. In recent years, the University has expanded its distinguished visiting scholar program, in which the provost’s office brings top minority candidates to campus for around a week to engage with the community. Adrienne Davis herself declined another school’s offer and joined the Wash. U. faculty after participating in this program.

Schools also have financial incentives to diversify their search pools, as more funds are provided to fly in minority candidates for interviews and the University pays a portion of the salary for the beginning of minority hires’ time on campus.

Larger-scale programs include the Mellon Mays program for undergraduate researchers, which aims to teach interested academicians the nuances of the field early in their careers; the chancellor’s graduate fellowship program, which creates a support network for graduate students of color; and a new summer institute in the Olin Business School, which received funds from the provost’s office to bring in minority Ph.D. candidates from other schools and get them thinking about a potential career at Wash. U.

But while the University might be casting a wider net with these approaches, the net remains shallow in its catch. Members of this past summer’s school-wide committee on diversity and inclusion related that their biggest takeaway from their investigation was that the University is stocked with small programs aimed at increasing diversity, but they aren’t properly integrated into the collective campus consciousness.

The splintering of those efforts makes them less effective than they could be were they centralized, community members argued, whereas collaboration could transform the whole of those initiatives to more than the sum of their individual parts. Davis’ vision of a cohesive, directed unit is still a dream, while, in the present, each program exists in its own independent bubble.

“We could be more powerful if all of us were working kind of inexorably toward the same goal rather than separately,” Nancy Staudt, the white dean of the law school and head of the summer committee, explained.

The University’s top leaders, however, dismissed concerns over intra-University communication.

“We don’t always have everybody knowing every thought that we have at any given time,” Holden Thorp said, before suggesting that rather than the administration, Student Life is likely the best source for providing such information to the community. “You writing your story is probably as good a way as we’re going to get…The more of this that’s in your article, probably the better for us.”

Thorp reiterated the hopes of other high-level administrators in expressing his desire for these programs to continue boosting Wash. U.’s numbers of black faculty. Progress has been occurring, he said, although not quickly enough.

He took a longer-term view of the issue, which is a perspective Michelle Purdy embodies, too. As a student, she pushed for rapid, large-scale changes, Purdy said, but as a longtime member of the University community, she too can see the bigger picture.

“As you get older, I think you come to accept that change happens slowly,” she said.

In the next installment in this series, we will take a closer look at the potential for change across a variety of issues associated with diversity and inclusion on campus, and how students feel about that rate of progress.

Additional reporting by Noah Jodice.

Read the rest of the “Invisible on campus” series here.