News

Invisible on campus: An introduction to the past, present and future of black oppression at Wash. U.

Read a letter from the writers here.

Ron Himes sits easy in his office on the third floor of the Mallinckrodt Center. The room is sparse—a lonely printer on the desk, a stack of books on the floor—with few memories from his past. He is a teacher and actor, not a historian.

But since the 1960s, when a wave of civil rights protests and student activism swept through college and university campuses across the country, Himes has been a member of the Washington University community. His experience came first as a member of a youth basketball team coached by Robert Johnson, the first chairperson of the University’s Association of Black Collegians (ABC), then as a student, a teacher and now an artist-in-residence.

Then-junior Kendall Maxwell marches toward the chancellor’s house in December 2014. The protest was one in a series of student activist efforts to open a dialogue with administrators about issues of diversity and inclusion.

As a sophomore in high school in 1968, Himes found himself shepherding groceries to student protesters camped out in Brookings Hall as part of an eight-day sit-in that yielded the first Black Manifesto, a foundational document that defined the demands of black students who felt underserved on campus. In his dealings with the ABC and subsequent experiences as a student on the Danforth Campus, Himes saw firsthand the grievances aired by the University’s sparse black population.

Sitting in his Mallinckrodt office more than 40 years later, Himes reflects on his past and present at the University. The school’s relationship with its black population isn’t so different from what he saw up close in the Civil Rights era, he says—just a few weeks ago, he hosted a group of pre-freshmen who echoed decades-old questions about the campus climate at Washington University.

“The things they were concerned about were some of the same issues, same questions that students have been asking over the years,” Himes said. Those concerns included the diversity, inclusivity and community support system at the institution they might attend.

It’s not just pre-freshmen, and it’s not just now. In 1978, a decade after the inaugural Manifesto, the Association of Black Students (ABS)—the renamed ABC—produced a second, writing, “We find it necessary in 1978 to reiterate our concerns either because they were not met in the past or because new ones have developed due to lack of attention and action.”

Fast-forward to the present, and current students across campus are voicing those same concerns and asking those same questions: Why does Wash. U. in 2015 look like it’s stuck in the 1960s when it comes to race relations and diversity and inclusion? Why is their school a persistent anachronism?

“Why do we have to keep talking about this?” senior Jon Williford, the president of ABS, asked in an interview before Thanksgiving break. “If people who just got here are having the same feelings as folks 50 years ago, whoa! Maybe this is something you should pay attention to. Maybe this is something we need to take a different look at.”

Over the course of the fall semester, Student Life spoke with nearly 50 University community members, comprising administrators, faculty, staff, students and alumni. We were searching for evidence of a plan to counteract the University’s history of homogeneity; we hoped to hear tangible, specific tactics that the administration will either continue or adopt to increase the low percentages of black students and faculty and to improve the campus climate.

Instead, we heard from deans who openly questioned whether Wash. U. has concrete strategies in place to increase its racial diversity, a director of admissions who shifted blame from her office onto student activists for not doing more to recruit black high-schoolers, and an administration plagued by false and inconsistent beliefs about where current efforts are falling short.

The Wash. U. community members we spoke with were in general agreement that the University has problems with race relations, and most on the administrative level spoke in platitudes about trying harder and the power of hope in improving the situation. But beneath this outward layer of optimism, many University leaders expressed frustration with the school’s slow progress—and black students and faculty shared similar doubts about the practical effectiveness of the school’s stated commitment to a more diverse and inclusive community. In the meantime, moreover, those community members say they feel silenced, uncomfortable and even unsafe given the current campus climate.

Similar sentiments and complaints have existed across the decades since Wash. U. abandoned its discriminatory admissions policy and racially integrated in the early 1950s. The University has struggled to confront those problems ever since.

Some administrators bristled when asked about the University’s historical relationship with its black population. Mahendra Gupta, the Indian dean of the Olin Business School, suggested he didn’t think we should address Wash. U.’s history of racial afflictions in our story but rather only how University leaders feel positive about the future.

“Looking backward teaches us, but we cannot just be held hostage to the past,” Gupta said.

But for black members of the University community, that teaching is important, too, because it informs our understanding of how Wash. U.’s current climate around race has been shaped and cultivated over decades of strife. As Jeffrey McCune, a black associate professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, said, “This is a historically and predominantly white institution, and what that means, often, is that it suffers from the same illnesses that our predominantly and historically white society suffers from.”

In a five-part series to be released over the next two weeks, we will take a closer look at what those illnesses are and if our school, so renowned for its medical expertise and innovations, has the right ingredients for a cure. Today, we delve further into the current context in which race operates on the Danforth Campus; upcoming segments focus on the school’s history of race-related activism, its struggle with diversity in undergraduate admissions, its tricky difficulty with faculty hiring and its ways forward, in 2016 and beyond.

* * *

As the University of Missouri #ConcernedStudent1950 protests against racism reached their crescendo last November, climaxing in the resignations of the school’s two highest-ranking officials, relief and excitement among student activists gave way to a new emotion: fear.

The night after the resignations, Mizzou’s Yik Yak—an anonymous social-messaging app—filled with threats of violence against black students. Popular hangout spots on Mizzou’s campus emptied, quads grew barren and numerous professors canceled classes due to the tense and fearful campus environment. Three students from other schools across the state were eventually arrested in connection with the threatening messages.

Halfway across the state and half a year earlier, Yik Yak posts with racist messages shed light on the underlying problems with racial attitudes at Washington University.

Students walking to class on the Danforth Campus on Feb. 9, 2015, exactly six months since Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Mo., found the campus wallpapered with printouts of racist Yaks collected throughout the year. The previous weekend had seen the performance of the annual Black Anthology drama production, which addressed Brown’s death and the ensuing unrest. The play in turn incited a round of messages attacking black people. One illustrative post applauded police officers for using blacks as target practice; another mocked Black Anthology for existing only because of affirmative action.

Interviewed a semester later, a number of black students said they weren’t surprised by the content of the messages, given the campus climate to which they had grown accustomed. And because their peers had already sprinkled such messages across social media feeds throughout the school year, the students weren’t shocked that the Black Anthology production had sparked a deluge of posts.

“You get used to it—but I think I’ve been getting used to it my whole life, too,” junior Andie Berry, one of the Black Anthology playwrights, said. “I mean, it sucks, but also it’s normalized. At this point, I’ve gotten so used to it that it barely registers most of the time, unless it’s something really awful.”

While Berry tried not to think about the content of the messages and instead focused on the positive feedback about the play she heard from friends, other students said they were overwhelmed with feelings of paranoia because of the posts’ anonymity.

Mimi Borders, a freshman at the time, said she felt “paralyzed,” didn’t go to class for two days and spoke with an advisor about leaving Wash. U.

“I can’t go to school here. I can’t go to this institution. I hate this place; it’s unsafe. I can’t thrive here,” Borders recalled thinking at the time.

For Kielah Harbert, also a freshman at the time, those messages were symptomatic of what she defined as her introduction to the Wash. U. experience.

“Do I feel safe here? No, because I don’t know if it was my peer next to me” composing those messages, Harbert said. “It’s so difficult feeling safe here on-campus.”

Harbert has younger siblings living in North St. Louis, and she said she questions whether she would want them to attend Wash. U. when they reach college age.

“Do I want them to have to experience what I experience—to feel isolated, to feel not wanted, to feel like you have to constantly think about your identity every single day?” Harbert asked.

* * *

Administrators roundly denounced the messages when they appeared on flyers around campus. “I’m horrified, saddened [and] perhaps naively shocked by what community members have said—and I’ll own that too. Thanks to all who downvote hatred,” Jen Smith, the white undergraduate dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, wrote in a Facebook post.

But black students weren’t shocked—rather, they saw the posts as mere manifestations of more pervasive problems on campus. While the University publicly highlights its efforts to increase the number of black students and faculty on campus, the school can be isolating and uncomfortable for those already here. Black community members interviewed for this story could consistently share experiences that made them feel excluded.

Wash. U. in recent years has been implicated in a number of incidents involving racial concerns. In 2002, an engineering student alleged he had received a lower grade in a course and suffered repeated slights during class due to racial discrimination. In 2007, a popular black assistant professor of history was denied tenure. In 2009, a social work student alleged he had been racially profiled by a Washington University Police Department officer.

Most publicly, in February 2013, a student partaking in a fraternity pledge event recited a rap song containing racial slurs in Bear’s Den, inciting a campus-wide controversy. The ensuing conversations helped spark the creation of the Center for Diversity and Inclusion and launch the Bias Report and Support System.

Rather than representing unique cases, these incidents “happen on a day-to-day basis,” Jon Williford, ABS president, said. “The special thing about these incidents is that they blew up. Otherwise, they’re the same disgusting, everyday things that need to go away.”

Such issues creep into the classroom, as well. On one memorable occasion, WGSS associate professor Jeffrey McCune recalled, another faculty member entered his class and, despite McCune standing at the front of the room, asked an accusatory “Who is the professor here?” Reflecting on the humiliating occasion in his office last semester, McCune described feeling “invisibilized” by the encounter and attributed it to the “rarity of black folk” in teaching positions.

“The feeling of being invisible on a campus where you work really hard and you love your students and you teach well and you do service and you do research is really disheartening,” he said.

* * *

It would be reductive and disingenuous to submit that there is a singular “black experience” on Wash. U.’s campus. Short of interviewing every black community member, such a broad designation is unreachable.

With regard to the need for campus activism around racial issues, artist-in-residence Ron Himes described a variety of perspectives that black community members embody.

“There’s certainly a contingency that thinks that everything has been addressed. There certainly is a contingency that thinks that everything is just fine and hunky-dory,” Himes said. “I’m sure there’s a contingency that thinks that things are just as f—ed up as they used to be, and ‘What are we going to do, you know—we’re still fighting the same old battles.’”

As Lori White, the vice chancellor for students who has studied within-group diversity among black students on college campuses, explained, “Typically when you read an article about black students in college, the article assumes there’s kind of one black experience.”

Such an assumption is flawed, White continued, but “on the other hand, I think there are some things that you will find are probably relatively common to students who go to an institution where they are not in the majority.”

For White, who is black, that commonality manifests as being cognizant at all times that she is a member of a minority group. “There’s just this feeling, I think, every day, that you’ve got to put on this armor in order to kind of confront the rest of the world,” she said.

Not all black community members interviewed for this story agreed that they felt the need for armor. Richard Souvenir, a former Wash. U. undergraduate and Ph.D. student and now an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, said he didn’t notice racial differences on the Danforth Campus until he was a graduate student.

But they spoke uniformly about experiences of bias due to their race, such as a variety of microaggressions—or everyday slights that communicate hostile messages toward others based on their identity—that “over time become cumulative and deeply irritating,” Vice Provost Adrienne Davis said. Among current students, such incidents include classmates assuming they’re on campus due to affirmative action, grouping “all black people” together in conversation and exhibiting less friendliness when walking near each other on campus.

“I’ve gotten in the habit of walking further behind people who don’t know me,” Berry said, because she thinks, “‘OK, they’re going to glance, and they’re just going to see brown skin and they’re going to see my hair and they’re going to see dreadlocks, and they’re not necessarily going to register height, weight, the fact that I’m female, any other factors.’”

* * *

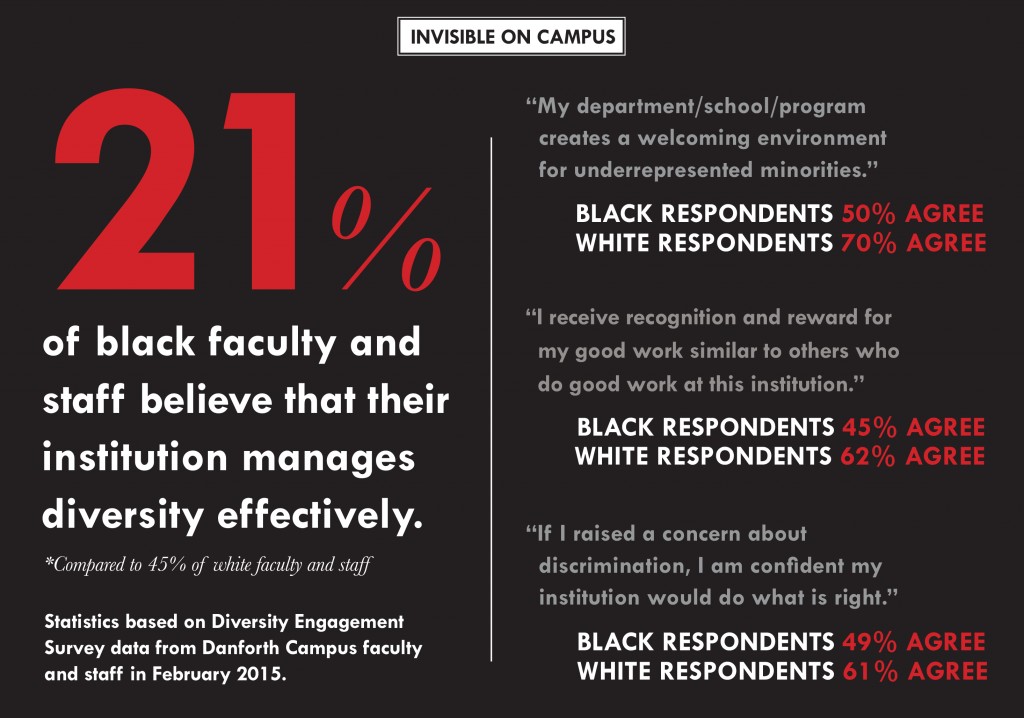

The data on racial incidents on campus is limited but supports the anecdotal evidence from students and faculty members.

In the three full semesters since its launch in January 2014—data for fall 2015 is not yet available—the Bias Report and Support System has received 126 reports, more than half of which included a racial component. In a campus-wide survey of undergraduates in spring 2014, black students were much more likely than their peers of other racial backgrounds to say that they had experienced an incident of bias on campus on the basis of their race.

Senior faculty and administrators said that, despite their prominent positions, they still experience racism “all the time,” that offenses happen “routinely” and that it is “common” for them to feel belittled by their peers or the broader campus climate.

These campus figures also explained that the issues they observe at Wash. U. run parallel to the ones they experienced as students or junior professors 10, 20 and even 30 years ago.

“To effect the kind of change that really matters and makes a difference means that institutions have to make some drastic changes themselves,” Himes said. “The wheels of the big institution turn toward progress; we hope all the time, but some turn faster than others.”

“It’s really disheartening,” Davis added. “It doesn’t seem that things are changing.”

Next in the series, we’ll explore how things have—or haven’t—changed as we detail the history of diversity and inclusion of black people at Washington University, from the school’s founding in the 19th century to the present day.

Read the rest of the “Invisible on Campus” series here.