Forum | Staff Columnists

Dead letters

We who work today by accident in paper and ink…should be happy. For we know—we must know—that the words and pictures and ideas and images and notions and substance that we produce is what matters—and not the vessel that they arrive in.” This is taken from a talk delivered at Columbia University’s School of Journalism in the year 2000, by the then-editor of Time, Inc. and future public editor of The New York Times, Dan Okrent. It was a speech entitled “The Death of Print.” In this speech, Orkent made a pithy ode to the enduring nature of journalism, confident that whatever happened, the people would always need the news. But a decade later, this death is undeniably upon us.

The entire publishing world, long overextended and debt ridden, has begun to painfully contract. A few daily papers have officially ceased to exist in physical form, and dozens of magazines have folded. And perhaps fittingly, it is the grim optimism of Okrent that is most often invoked among many journalists and their families when I hear this current crisis discussed. Try as I might, I can’t see any way toward agreeing with them.

What confronts us is the grim reality that there is nothing that print journalists produce that cannot be produced better and cheaper on the Internet. This does not, in and of itself, spell journalism’s doom. Print journalists are still professionals, schooled in an art that most of us deem essential to any free society. They must merely adapt, goes the Okrentian line. And taking stock of current digital efforts, like The Daily Beast—started by former New Yorker Editor Tina Brown—an earnest if uneven attempt at “news curation,” or more established successes such as The Huffington Post or the Drudge Report, one might believe it. They are, after all, chiefly comprised of articles or links to articles written by people whose chief aim is to educate, analyze or explain. Perhaps it is merely a matter of abandoning one vessel for another.

But this too is mere hopeful axiom. The net is young, very young, and it is ever changing. Any similarity between current news offerings should not be taken as an official benediction of the digital age. We should remember that the very newspapers we read took several hundred years to become the avowedly independent, neutral and boldly enterprising content gatherers we now revere. In between came the invention of such notions of copyright, free speech, libel law and other institutional innovations. Some look upon these ideas as milestones of human progress. It’s hard to see them now as anything more than minor tweaks in a defunct software. For their survival in the digital age is no assured thing.

Because the net, unlike movable type, has the power of rapid and unbounded evolution. And it is a ruthlessly opportunist. Any slightly more personalized, more socially amenable, more efficient or just plain prettier method of disseminating information is heedlessly adopted in droves. Twitter, the short-form blogging apparatus that most mocked as a farcical and masturbatory exercise in narcissistic over-sharing, has become a cultural phenomenon. Facebook recently made an attempt to purchase it. Obama used it for his entire campaign and uses it still. And it took two weeks to build and implement. One year from now, it could be as dead as Ruckus. There is simply no way to tell. What is apparent is that the net is rudderless and will probably remain so throughout the foreseeable future. And in its many metamorphoses, I struggle to find any systematized format that hews to any notion of craft. Bloggeristic integrity is not an idea I expect to come across any time soon.

So, I hold no stock in the assumption that just because any given format that happens to resemble newspapers is currently surviving on the Internet, its future is secured. To really square this question, we have to ask ourselves if there is anything, anything at all, that journalists, as journalists, can provide better than anyone else. We can no longer expect to be the guild of the worthy opinion. The New York Times could shutter up tomorrow, and we could still get Paul Krugman’s ideas on the stimulus package. We cannot expect to be the ones who break the real scoops. TMZ and Matt Drudge are far less encumbered by either scruples or taste, while more civic-minded sites like Follow the Money allow us a dimension of congressional accountability that even the best papers could not ever hope to effect. Can we call ourselves the voice of the people, when they are learning, for better or worse, to speak for themselves? We are left with little more than our debunked methodologies and our empty commitment to the truth, or its best approximation. In that I must disagree with Okrent: Compared to the vessel, they could not matter less.

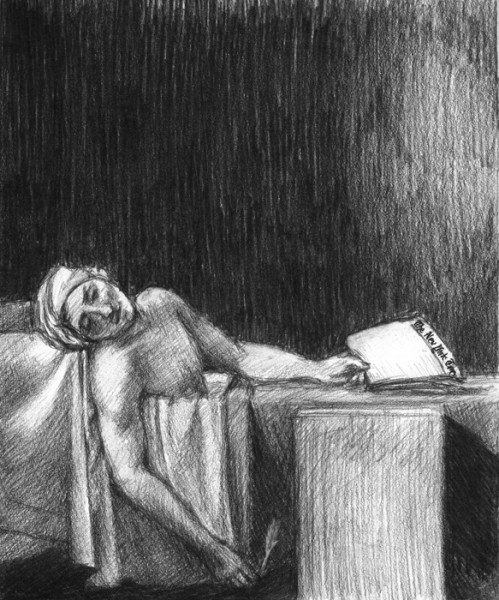

(Godiva Reisenbichler)