Men's Basketball | Sports

‘We see him as a superhero’: Justin Hardy’s unlikely return to the basketball court

Justin Hardy directs traffic during a recent game against New York University (Photo by Curran Neenan / Student Life)

When former University Athletic Association Rookie of the Year Justin Hardy came to campus in September, he couldn’t jump 10 inches off the ground. The Washington University men’s basketball forward couldn’t run up and down the basketball court three times. When he began shooting around with freshman Hayden Doyle for the first time, Hardy was far from his former explosive power. None of his teammates were sure if Hardy would return to playing minutes at all after watching him undergo chemotherapy all summer. “He wasn’t in game shape, obviously,” Doyle said.

When Hardy first started practicing with the team in October, he couldn’t dunk — he couldn’t get the ball over the rim. Still, he was doggedly persistent with his conditioning program, taking his time with the exercises that would have been his warmup six months prior. He got to the point where he was doing the same exercises as his teammates, and a month later, teammate David Windley looked over to see Hardy outlifting him.

Now, while still in treatment for his stage four stomach cancer, Hardy is back to scoring just under 11 points per game — the second highest on the team — and was an integral part of the No. 3 Bears’ early-season, 13-game winning streak. “The progress he’s made is mindblowing,” Doyle said.

***

Hardy refuses to lose. He’ll play tricks of the card game Hearts for hours, banding together with his friends to leave someone with the unlucky queen of spades. He graduated in December after just three and a half years, refusing to take a lighter load to accommodate the busy schedule of basketball. And this fall, he’s fought against every odd to return to WashU beside his teammates to compete at the upper tier of Division III basketball.

Back in March, when teammate David Windley looked up the street to an ambulance whizzing past him, he hoped that the loud sirens were a bad coincidence. Sure, he knew that his roommate and teammate Justin Hardy wasn’t feeling well, but he dismissed it as just strange timing. Then, from blocks away, he saw the vehicle stop at his house, and by the time he got home, Hardy was being ushered into the ambulance.

At that point, no one knew what was wrong. Hardy wasn’t a stranger to waking up a little sore after workouts. He’d come back from injuries and maxed out reps enough to know the tiredness that comes from pushing his body to its limits. But one day in late March, he opened his eyes from a nap and felt shooting stomach pains. After an unproductive trip to urgent care and eventually the hospital — where they told him that he was just dehydrated — he returned to the hospital with worsened symptoms. After days of pain, doctors found a perforated ulcer in his stomach and performed emergency surgery to repair it. Then, Hardy woke up after surgery to more bad news. The doctors had found a sizable tumor in his stomach. They ran a biopsy and pathology on the mass, and after days in the hospital, Justin Hardy was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

The first person Hardy called from the hospital was his dad. Then he broke the news of his diagnosis to his closest friends on the team over Facetime. All of Hardy’s roommates huddled around one phone, and they initially didn’t know anything except for that something was seriously wrong. His three best friends on the women’s soccer team sat in silence even after he hung up, tears streaming down their faces. “It just took my breath away, it was so unbelievable,” said Kally Wendler, one of Hardy’s closest friends.

Hardy went back to Chicago to figure out a plan for treatment at University of Chicago’s oncology center. Surrounded by his family, he went through test after test, talked to doctors, and explored his options. His first day of treatment “was a bittersweet day of ‘Oh, we’re really starting this,’” Hardy recalled. His distraction that day was WashU baseball’s trip to the College World Series. “Baseball was my entire existence last spring,” Hardy said. “The only thing getting me through that day was that I had [the baseball team’s] game against St. Thomas.”

Hardy wasn’t even considering the possibility of returning to the court until his oncologist brought it up during a routine check-in in late July. Over the Zoom screen, Hardy paused as he thought about it. At the time, he had a port in his chest and treatment was still a biweekly battle — “Is that even an option?” he questioned. Sure, his doctor said. Granted, he added, there was no way Hardy could return to a high competitive level, but there was no harm in shooting around.

The most the senior had done since March was walk his dog around the block. Still, under the hot Chicago sun in the weeks after the late July appointment, he went from power walks to unweighted squats, in constant pain with every exercise. His muscles had morphed into something that he didn’t recognize, and the first two weeks returning to conditioning were the hardest mentally. But slowly, he started to lift. He transitioned from walks around the block to runs around the neighborhood. His high school coach opened up the gym and let him shoot around with the younger players. In mid-August, he didn’t have enough power to get the ball from the three point line to the rim.

At first, Hardy wasn’t sure if he wanted to return to the court competitively. “The biggest fear you have is that ‘I’m going to try this and I’m going to fail, right? I’m never going to get back to the point where I’m capable of playing,’” Hardy said. “I had to get over the fact that, yeah, that’s a very real possibility.”

As the senior started to feel more physically capable, his first step once he returned to St. Louis in September was to go to head coach Pat Juckem to suggest the possibility of returning in some facet for the team. Maybe, he proposed, he could be the best scout team guy in Division III. Maybe he could compete for a rotation spot. Juckem hadn’t considered the possibility, but still, the news didn’t really surprise him. “For those of us who know Justin, we weren’t really that surprised with his will, his toughness and determination,” Juckem said. “If there’s anyone built to beat this, it’s Hardy.”

Hardy came to the Athletic Complex on Oct. 15, the first day of practice, with his jersey on. His doctors performed a small surgery that bought him five weeks without treatment at the beginning of the season, and then he reverted to IV chemotherapy. He then balanced his last semester of school with treatment, in the doctor’s office every Monday and then back on the court on Wednesdays with two days of practice before weekend games.

Once he stepped on court for the Bears, Hardy slowly began to regain some of his former strength. Simple skills that once were second nature were initially still a struggle — the senior was tricking wide open layups. It was growing pains for him, but by the fourth game of the season, he had a mental switch flip. Against Dubuque, he scored 28 points, matching his career high from freshman year. Two months after Hardy couldn’t reach the rim, the team played Illinois Wesleyan and Hardy took possession of the ball at the top of the key. With a dribble and a yell, he dunked against Wesleyan’s all-American center.

“I was so emotional about it all. He just continued to amaze in so many ways — what Justin has already done this year is a miracle,” teammate Jack Nolan said. “I was in tears after the game, hugging that kid. That game, that moment — I’ll never forget that.”

***

Right now, Hardy can only look ahead two weeks at a time, and it’s driving him crazy. He’s a planner: he likes to have things lined up. But now, he has no idea what happens after he finishes his chemotherapy treatment. He’s seeing diminishing returns from the therapy, which he describes as “maintenance as opposed to a cure” — the tumor has started to adapt, which means that now he has to start considering other options.

Hardy is a numbers guy. He majored in accounting and finance, which means that he can’t ignore the odds that were given to him. Plus, he said he doesn’t really believe in miracles: “There’s no reason for me to think that I’m an outside exception.” Still, there are a lot of unique factors in his diagnosis. The average age of diagnosis in stomach cancer is 68, and Justin is a 21-year-old athlete with seemingly everything going for him. His diagnosis was so unlikely in the first place that he has hope that he can also defy the odds with his outcome. “Mentally, I’m not at the point where the bad things are really bad,” he said. “There’s nothing at this point that can really rattle me.”

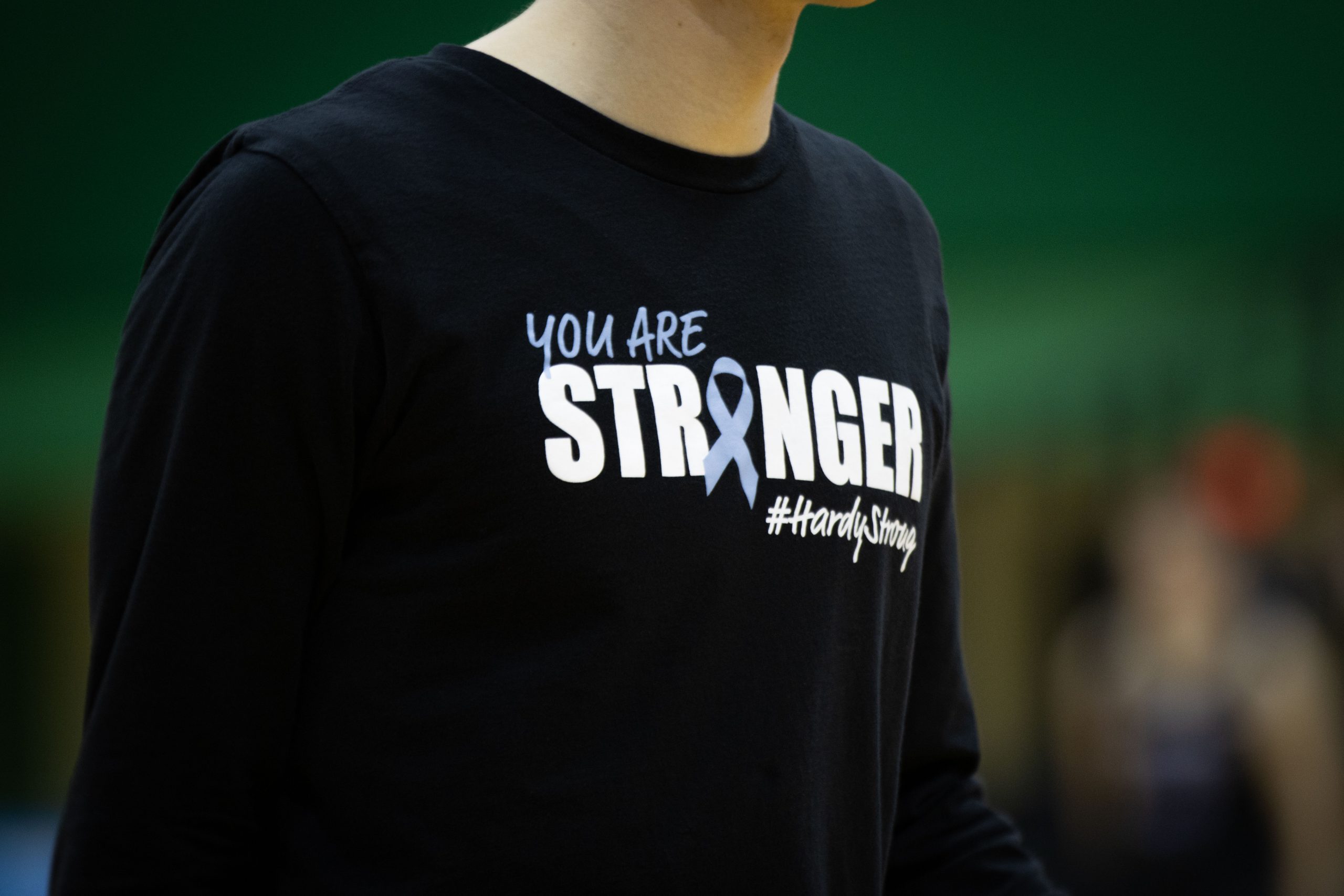

A warmup shirt worn by Hardy’s teammates and the coaching staff. (Photo by Curran Neenan / Student Life)

His optimism is infectious for his team; he’s struggled through dark moments over the past six months, but he’s been intentional about putting a positive spin on his situation. “The love was always there but now that he’s gotten to a place of pure happiness and joy, that love is so much more evident in his life,” said Nolan. “There are people who search for that their entire life and never find it, but that’s the best way to describe that kid.”

A lot of things have stayed constant for Hardy over his three and a half years at WashU. He’s still living with his best friends and bringing out his competitiveness in games of Hearts. He’s relentlessly supportive of his friends in their successes — like his former roommate Caleb Durbin getting drafted for Major League Baseball’s Atlanta Braves — while also supporting them in their struggles. “I look up to him in a million ways, but mainly because despite his circumstances, he’s just been so unrelenting in our friendship,” Wendler said.

Hardy has been so externally strong that in September, a freshman on the basketball team asked Windley, “Wait, Justin has cancer?” Windley had to explain that his teammate had been doing chemotherapy and treatment all summer.

Even during the summer, his closest friends struggled to get a sense of Hardy’s physical and mental obstacles because his optimism overshadowed everything else. Through his compassion for his friends, he redirected attention away from himself. “He has just never once made anything about himself. He is the most compassionate person in the sense that he is constantly investing in everyone else,” Wendler said.

At the beginning of the season, Hardy’s teammates thought that best-case scenario, he might practice with the team. But he defied their expectations by returning to the starting lineup; his competitiveness for the Bears was completely unprecedented. Hardy described himself as the most unreliable player in the country right now, but those around him see him differently. Juckem described him as the most reliable person he knows, while Doyle sees him as an older brother. “Everyone on the team, regardless of age — we all see him as just a superhero,” Windley said.

Basketball has always been a passion for Hardy, but as he’s come back this season, it’s become a refuge. He’s been able to express his love for the game with contagious energy that has impacted the whole team’s outlook; it’s given them perspective on what it means to have the privilege of stepping on the court every day. His team feels that they’ve received ten times what they’ve given him.

“Justin Hardy has changed my life like six different times since the diagnosis,” Nolan said. “There’s a lot we can take from how he’s lived, and how he’s living — the courage and the strength he’s had throughout all of this.”

At the end of the day, Hardy argues that this WashU Basketball season — with the team 14-3 so far — isn’t about the adversity he’s overcome. It’s not about the incredible journey from a hospital bed to the basketball court. “I don’t want this to be the Justin Hardy show. It’s not about me: that’s our team motto this year,” said Hardy. “It’s not about any one of us, but together we can do something really special.”

More features from the Student Life sports section:

Three-time Paralympic champion Kendall Gretsch’s journey from Olin Library to Tokyo gold