Scene | The Fight for Pell

Low on Pell: WashU and the U.S. News & World Report Rankings

This article is part of “The Fight for Pell: The History of Socioeconomic Diversity at WashU,” a Student Life series that documents the long struggle for increased awareness and support for Pell-eligible students. Read the letter from the author here.

“When I first started at Washington University in St. Louis, the idea of it becoming need-blind wasn’t even on the table,” said Lauren Chase, the former president of WU/Washington University for Undergraduate Socioeconomic Diversity (WU/FUSED).

Like Chase, many higher-education experts would argue that financial-based arguments against need-blind admissions are unfounded. Claims such as “Our endowments are restricted” or “Low-income students accepted offers from other top colleges” are a distraction from the main concern. The main concern regards how admitting Pell-eligible students would affect WashU’s goal of climbing higher in the U.S. News & World Report college rankings.

According to Stephen Burd, a senior writer and editor with the Education Policy program at New America, the focus on rankings and salaries for many prestigious universities prevented WashU from entertaining the idea of need-blind admissions in the first place.

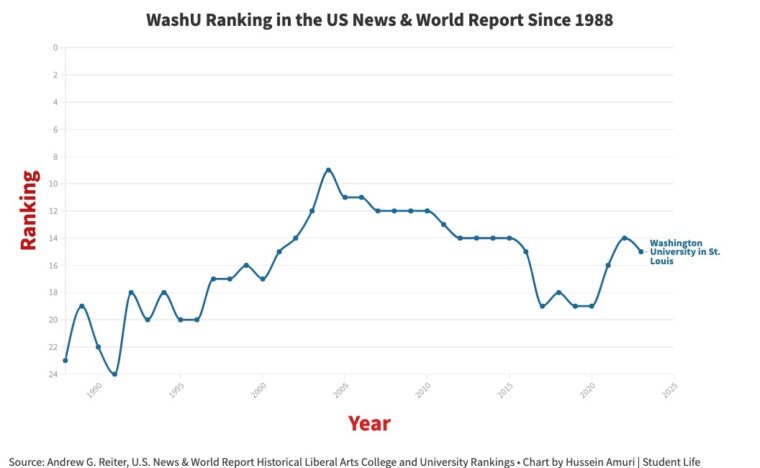

“My sense was that there was definitely worry about academic standards, and probably rankings [falling off]…which I think is really unfortunate,” Burd said. “I think the U.S. News rankings have a really pernicious effect on [Pell-eligible numbers]. It rewards schools for being more exclusive. That especially affects the schools that are striving to move up the chain, and WashU went through that process in the ‘80s and ‘90s.”

The U.S. News rankings formula is complicated. However, According to experts, it involves three major criteria. The first is students’ performance on standardized admissions tests, such as the SAT or ACT, which are largely tied to their family income.

A 2017 Upshot article by the NYT showed that the median family income at WashU is $272,000. Furthermore, the Upshot disclosed that about 3.7% of WashU students came from the top 0.1% of the income bracket, 22% from the top 1%, and only <1% from the bottom 20%. These numbers were some of the lowest in the country.

The second major criterion for the formula is having a lower acceptance rate — a feat that many colleges achieve by accepting and enrolling more students from their early decision admissions programs, programs that historically enroll primarily wealthy students who attended private high schools. In a written email to Student Life last spring, the WashU Admissions Office stated that the University enrolls about 60% of each incoming class through its early programs (Early Decision I, Early Decision II, and QuestBridge Match).

“The students who are most likely to apply early decision to a college are students who go to independent private schools and international students. What do those students typically have in common? They’re not Pell-eligible students,” said James Murphy, Deputy Director of Higher-education Policy at Education Reform Now.

While Murphy was critical of early admission, he did note its benefits when it comes to recruiting students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds.

“Early decision can be a force for good; colleges can use it to prioritize low-income students,” Murphy added. “So I don’t think early decision in and of itself has to be harmful to both racial and socioeconomic diversity. But it certainly would be important for a university to open the books right and let the world see if that’s indeed how it actually works.”

The last major criterion in admissions decision-making is alumni giving — a process that incentivizes universities like WashU to appease alumni by accepting their kids, creating a legacy-admissions system.

“The people who benefit from legacy preferences are overwhelmingly wealthy and overwhelmingly white,” Murphy said.

For Murphy, here is where the problem lies. While he applauds the university for increasing its Pell-eligible numbers from 5% in 2014 to 20% in 2023, he states that more can be done on this matter. Specifically, he advocates for a detailed disclosure of some of the numbers the University advertises, such as the percentage of each incoming freshmen class that is first-generation and low-income.

“I think WashU can be proud of its record of improvement; I don’t think it can be complacent about that record of improvement,” Murphy said. “A lot of colleges like to talk about how many first-generation students they admit. But how many students are first-generation and low-income?”

Rankings often come up when the issue of Pell-eligible students is discussed, but the U.S. News ranking system can be a force for good on the issue of socioeconomic diversity — especially after some of the small reforms it has undergone in recent years. Specifically, U.S. News added a component for Pell-eligible students — around 5% of its formula. Other institutions like William and Mary made a push on enrolling more Pell-eligible students; Murphy theorized that WashU may have done the same. “You’ll never get anybody from the administration to admit that, but they’re going to pay attention,” he said.

Closing the 2010s, WashU did start to climb the U.S. News rankings, and that positive mobility did correlate very well with the increase in Pell-eligible numbers that the university was seeing.

Another important component that Murphy notes about the U.S. News rankings being a force for good has to do with the issue of class size. “Is it using its endowment to accommodate more students?” Murphy said. “Or is it staying small to hold on to that low admit-rate, which is so important for so many colleges and alumni?”

As of right now, the current WashU acceptance rate is 13%, with a 15.54% average rate over the past nine years. “Why do we need a society where [universities and colleges have an admission rate of 13%]?” Burd said. “I think that we’ve seen that there’s just been such a focus on exclusivity as being this metric of quality: the more exclusive you are, the better you look.”

“There’s no way [WashU] is ever gonna not be a majority wealthy [institution]. But it does seem, for all my cynicism [and] for the reasons they got involved in this in the first place, [that] I do think that it’s very positive that they have continued and gone beyond what they initially pledged,” Burd said. “I hope that they continue and keep striving to make [their campus] more diverse.”