Scene

Rooted in St. Louis: Professor Gayle Fritz illuminates the history of St. Louis human-plant relationships at Cahokia

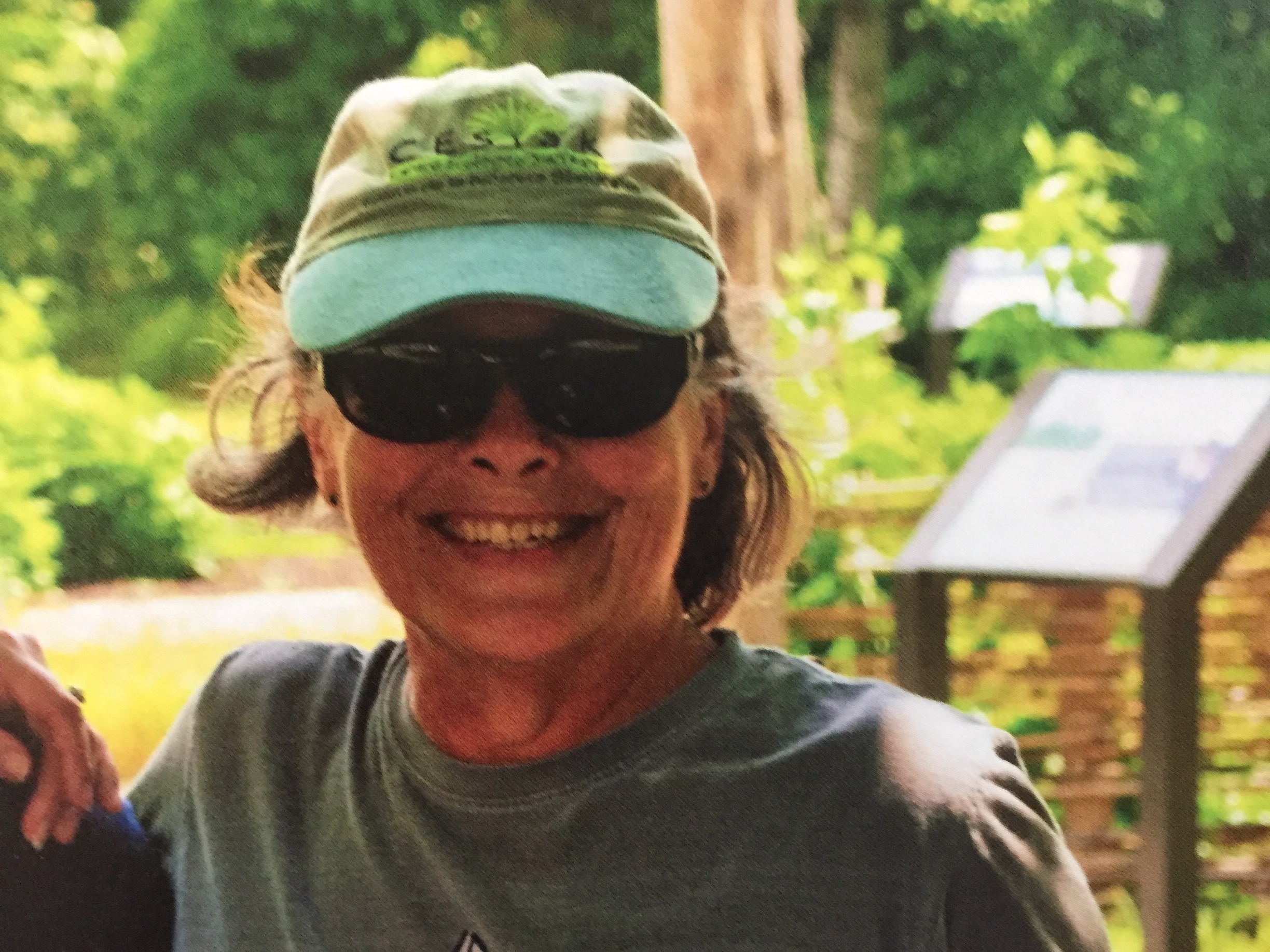

Professor Emerita of Archaeology Gayle Fritz has studied ancient plants around the world, including at the Plum Bayou Garden at Toltec Mounds, Arkansas. (Courtesy of Gayle Fritz)

Humanity and plants have been partners for millennia, and every crop has its history. But not all of our leafy partners get their due credit; indeed, many of them have been lost to time.

Gayle Fritz, professor emerita of archaeology at Washington University, has conducted extensive research to uncover the history of these “lost crops.” Fritz is a retired anthropological archaeologist with a specialization in paleoethnobotany — a branch of archaeology which studies human-plant relationships.

How does one study plants that no longer exist? In short: burnt seeds.

Paleoethnobotanists sift through ancient dirt at archaeological dig sites to find seeds preserved by partial burning. Once back at the lab, they spend much of their time studying minute differences in seed morphology.

Fritz’s interests lie primarily in eastern North America, but her studies have crossed the globe. Her book, “Feeding Cahokia: Early Agriculture in the North American Heartland,” outlines the agriculture of the pre-Columbian Missouri Mound Builder society, which was located near modern-day St. Louis.

Research into contemporary Native American societies, the descendants of the Mound Builders, has informed Fritz’s research. She has been able to reconstruct some of the dishes that might have been eaten at Cahokia, including approximated recipes in her book.

“We go back thousands of years in our appreciation of societies in North America,” Fritz said. Before the development of the “Eastern agricultural complex” of crops and the plant domestication in North America 4,000 years ago, she explained, Indigenous people lived in highly mobile hunter-gatherer groups.

In analyzing contemporary northeastern tribes’ cultural relationships to farming, Fritz has determined that farms of Cahokia came to be dominated by female labor. “They were the botanists; they were the ones who understood the plants.”

Fritz recounted an interview with a woman of the Hidatsa tribe, a culturally similar tribe in South Dakota. When asked if men ever help on the farms, “she laughed as if it were the funniest thing she ever heard.” Young men did go out into the fields sometimes, she added, but it was usually just to flirt with women.

By 2,000 years ago, the agricultural system used by Cahokia was firmly defined and standard across the highly developed Hopewellian Mound Builder society, the wider cultural group to which the people of Cahokia belonged. At its height, this group — named for the Hopwell mound group in Ohio — stretched from the Great Lakes to Florida.

Some of the crops that made up this complex are still grown today; sunflowers made up a major part of their diet, as well as squash. Others are less familiar: sumpweed, little barley and erect knotweed did not have the staying power of corn and beans.

Sumpweed seeds were a staple part of the Cahokia peoples’ diet. (Courtesy of Gayle Fritz)

One of the unsung heroes of Mound Builder agriculture was the chenopod. These seed crops have made a comeback in modern years, with Andean quinoa now regularly available in campus salad bars and healthy vegetarian meals. Domestication of chenopods happened independently in North America, though these varieties do not come down to us today.

Even as these crops have been lost to time, their relatives live on as weeds. Lambs quarters, also members of the chenopod family, will especially prevail; you can catch growing up from the cracks in the sidewalk on Delmar Boulevard. The line between weed and crop has not always been as clear cut as it is now, and Fritz suspects that these edible weeds were tolerated up to a point.

“The impact that it had on the diet was huge,” she said. “There would have been much more nutrition that was added to the diet from these plants.” Fritz tolerates these plants in her own garden as well, adding that “it’s a lesson for our food production of the future, right here in Missouri and Illinois.”

Alienated as many living in modern urban and suburban areas are from farming, it is difficult to overstate the centrality of agriculture to ancient peoples. Fritz described the cultural attitudes toward farming as “a highly spiritual connection to individual plants.”

While spending hours looking at burned seeds underneath microscope magnification may seem like tedious work, Fritz makes it sound romantic.

“I cannot imagine anything more beautiful than some of these seeds,” she said “Frequently, you find wonderful surprises.”