Scene

Black History Month: Notable moments since the first Black Manifesto

In the second part of our two-part series on key moments in Washington University’s Black history, we will examine events from the 1968 publication of the first Black Manifesto through the present day.

The first Black Manifesto was published in December 1968, reflecting students’ response to racial harassment, increased violence on campus and a possible assault of a Black graduate student, Elbert Walton Jr., by a member of the Washington University Police Department. Student Life reported in 1968 that the incident occurred following a confrontation over Walton’s lack of a parking pass. An article published in Student Life one year after the incident, in December 1969, recounts the events that followed: On the afternoon of that assault, Dec. 5, 1968, Black students occupied the security office in Busch Hall demanding justice for Walton.

The occupation moved to North Brookings Hall the following morning, at which time the Black Position Paper was released. On Dec. 11, the Black Manifesto was released. Negotiations with University officials, especially Chancellor Thomas Eliot, occupied much of the next week; the occupation ended on Dec. 14, after achieving confidence that the University would take what the Association of Black Collegiates (ABC) called, in a statement quoted in Student Life, “meaningful action” to address the issues raised in the Manifesto.

This Manifesto would be the first of many, with revised Manifestos released in 1978, 1983 and 1998. A detailed explanation of each version of the Manifesto, released by the ABC, now the Association of Black Students (ABS), can be found in “Invisible on Campus.” Its main demands were: an increase in Black faculty; an increase in the percent of Black undergraduates to 25% of the campus population, though this was reduced to 13% in later Manifestos; the creation of a Black Studies program, which was created in 1969 and given department status as African and African-American Studies in 2017; an increase in financial aid awarded to Black students; and greater sensitivity, both in terms of course material and campus environment, to the overwhelmingly white nature of the University.

Following 1968, the University’s Black population rose from under 2% to hover between 5% and 7%, numbers that would be maintained until 2015. Currently, the University’s enrolled student population, including both undergraduate and graduate students, is 10.7% Black.

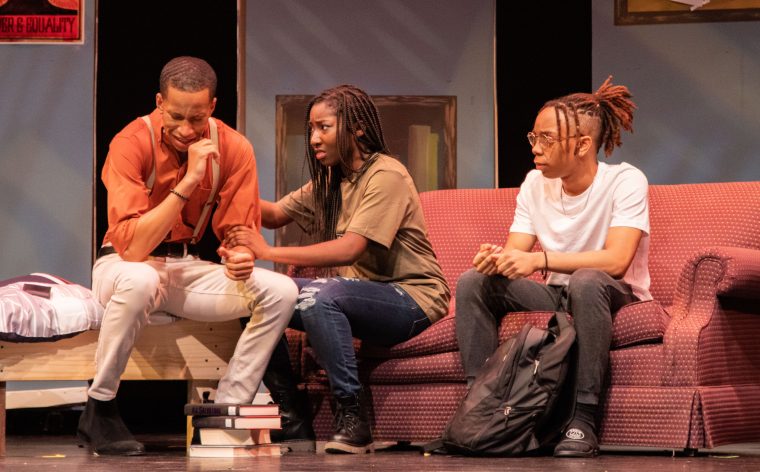

Black Anthology, the first cultural show at Wash. U., was founded by Marcia Haynes-Harris in 1989, as a space to showcase Black creativity within the Wash. U. community. Since 1990, the group has performed every year at the start of Black history month with a production examining the Black experience in America. The show celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2019, at which time Student Life ran a series called “The Road to Black Anthology,” examining the show and those involved in its production in more detail. One word that consistently came up was “community.”

“Invisible on Campus” was published during the spring of 2016. At that time, less than two years had passed since Michael Brown was shot to death in Ferguson. The University had just celebrated its second Day of Discovery & Dialogue (now renamed the Day of Dialogue & Action).

It is now the spring of 2020. The #BlackLivesMatter movement began seven years ago, and credits the events in Ferguson in 2014 with galvanizing it into the global organization it is today. The Center for Diversity and Inclusion has just celebrated its fifth anniversary. The University’s sixth annual Day of Dialogue & Action took place this past week.

Part five of “Invisible on Campus” discusses a pilot program for a mandatory diversity-focused undergraduate course. At the time, this program consisted of an optional class filled with 150 randomly selected freshmen. Now, this class is mandatory for students in Arts & Sciences—the Social Contrasts core requirement was implemented for students matriculating in and after 2017. However, this course does not have to focus on race. As listed on Wash. U.’s website, the course can cover topics about “race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, ability status or other categories.”

We now have a new chancellor, Andrew Martin. In his first act as chancellor, Martin announced the WashU Pledge, a promise of free tuition to local Pell-eligible students made with the goal of attracting more students from Missouri and Southern Illinois to Wash. U. Currently, 90% of undergraduates come from out of state, and 65% from more than 500 miles away. This pledge may function as more than just a draw for locals — it may be a push that causes Wash. U.’s demographics to start to look a little more like those of St. Louis. In marked contrast to the University’s population (10.7% Black), and that of the state of Missouri (11.5% Black), nearly 46% of St. Louis’ population is Black.

That’s not to say the University has suddenly become a perfect and welcoming environment for Black students in the last four years. Things are slowly improving, but there have still been major recent incidents of racial prejudice.

In July 2018, a group of 10 Black incoming members of the class of 2022 visited a local diner. After leaving, they were racially profiled by neighborhood police and accused of not paying for their meals even after producing receipts. In an email to the student body, July 31, Student Union president Grace Egebo called this type of profiling “devastatingly common.” An increasing amount of robberies in neighborhoods near campus in recent semesters has led to increased police presence, which some Black students have stated makes them feel unsafe.

These are just two examples of the many and varied ways in which the University’s history as a segregated institution and current status as a predominantly white institution impact its Black population. Black history month ends this weekend. Our series on Wash. U.’s Black history ends here. We have entered the present — the history that is currently being written. What remains to be seen is where we — the University, the country — will go from here.