Campus Events

Van Jones links social issues to the environmental, inspires activism

Environmental and human rights activist Van Jones connected racial equity and criminal justice reform to environmental sustainability and the growing green economy in his speech to a crowded Graham Chapel on Monday night.

Jones—a New York Times best-selling author, CNN political contributor, Yale University-educated attorney-at-law and previous green jobs advisor to President Barack Obama—used his life’s landmark moments to frame the broad issues of race, criminal justice and sustainability, making these issues more personal and localized for attendees.

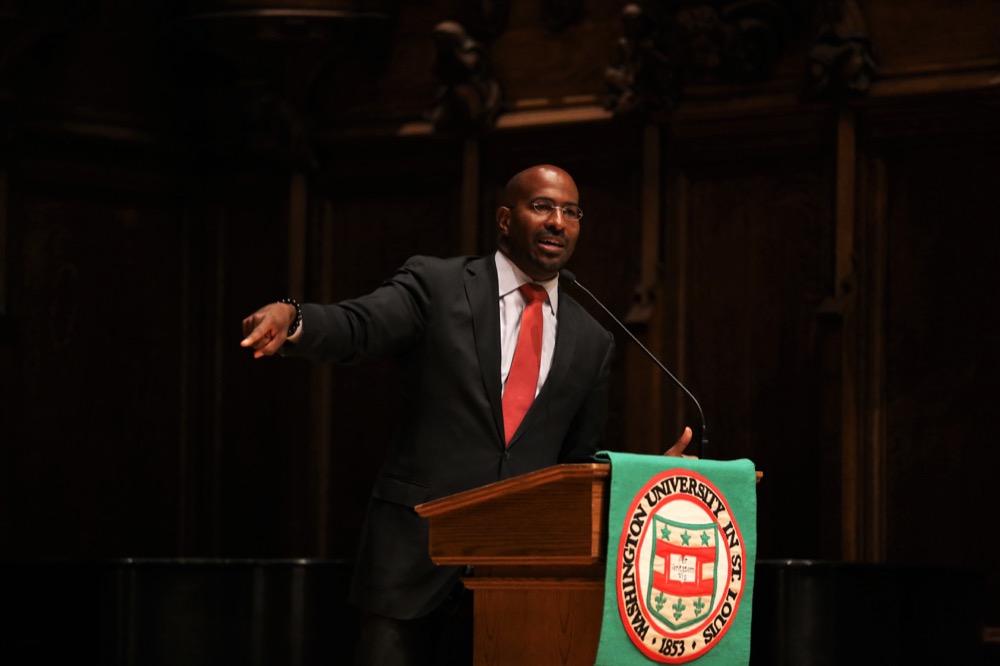

Jordan Chow | Student Life

Jordan Chow | Student Life Activist Van Jones speaks at Graham Chapel on Tuesday night. Jones spoke on the interconnectedness of the environment and community, emphasizing change through solidarity.

Co-sponsored by the Office of Sustainability, Environmental Studies and Missouri Gateway Chapter, Jones delivered his talk “Green Jobs, Not Jails” as part of the Student Union’s Trending Topics speakers while also kicking off this fall’s Assembly Series.

Through relying more heavily on narrative rather than pure statistics to move his audience, Jones began what became a nearly two-hour talk with striking data about the United States.

“We have only 5 percent of the world’s population, but we have 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, we are responsible for 25 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases, and we use 20 to 35 percent of the world’s resources,” Jones said. “Is there a connection?”

He recounted volunteering at the largely black housing projects three blocks away from his school. There, he noticed that the black youths in the community, often people of lower income, were being incarcerated more frequently and more severely than their white, wealthier counterparts at Yale University for identical drug crimes.

“I remember talking to my dean: ‘The Yale kids get into trouble, they go to rehab; poor kids get into trouble, they go to prison,’ I said. ‘Why?’ He says, ‘Well, Van, while those kids are drug pushers, drug dealers, our kids are just experimenting with drugs.’ I said, ‘You know, sir, I see no such distinction in our law or our constitution.’ I was pissed,” Jones said. “I grew up with the idea of liberty and justice for all, and it was a fraud.”

In his efforts to address the imbalances he saw, Jones said he developed the idea that new jobs in the growing industries of renewable energy and organic food could provide the beginning of a solution. According to Jones, green jobs and products could provide the disadvantaged a way out of poverty, criminal trouble and unhealthy and unsustainable lifestyles, if only people could work together.

Jones finished his lecture by building off of the traditional notion of sustainability, connecting the issues he saw in the environment with those in the communities he had seen and relating them back to his own humanity.

“Open your heart just a little bit more every time it breaks,” Jones said. “Your heart is a muscle. If you keep stretching it, it gets bigger. It gets more capable of holding more people, of holding more ideas, and helping more. At some point, it starts to get contagious, this idea that we don’t have disposable anything: it’s all precious. We don’t have disposable products and resources, and we don’t have disposable children or neighborhoods either. It’s all precious.”

Following his lecture, Jones took questions from the audience.

Second-year graduate student Eli Horowitz asked Jones about pushing utility providers to move from fossil fuels to clean energy, which is the essence of Horowitz’s new environmental initiative called Seize the Grid.

“The most shocking thing to me was that Van Jones came out and endorsed my campaign,” Horowitz said. “For me, the big thing was that he called on Wash. U.’s administration to publicly call for 100% clean energy for our school.”

Other students felt that the talk showcased sustainability’s inherent intersectionality.

“[Most people] asked what they could do to help and to make a difference. That’s when you know someone’s made an impact, when people immediately want to take action and follow their lead,” sophomore Sarah Spellman said.

This was exactly the result for which senior and Student Union Executive Advisor for Sustainability (EAS) and senior Nick Annin had hoped.

Annin spearheaded the initiative to bring Jones onto campus, though he credits his predecessor in the EAS position, Emma Searson, for laying the groundwork.

“I think Van was a phenomenal choice… Not only did you receive wisdom, but you received guidance,” Annin said. “I think he did a really good job talking about…all the vast intersections between those that oftentimes aren’t acknowledged, which is a huge disadvantage to any movement that is only focusing on this compartmentalized version of sustainability.”

At the end of the evening, Jones left the audience with an idea he took from African-American revolutionary history.

“If you’re going to get anywhere in St. Louis, if we’re going to get anywhere in America and in the world, we have to have solidarity,” Jones said. “That is what’s available to you: solidarity. Not charity, not pity, not guilt… Solidarity. All of you together. You can build the future you deserve.”