News

‘It’s actual people and their jobs’: How the NIH funding cuts would affect WashU

(Sydney Tran | Head of Design)

On Friday afternoon, the National Institute of Health (NIH) announced a $4 billion research funding cut spearheaded by the Trump administration. A federal judge temporarily paused the cut nationally on Tuesday following lawsuits filed the day before.

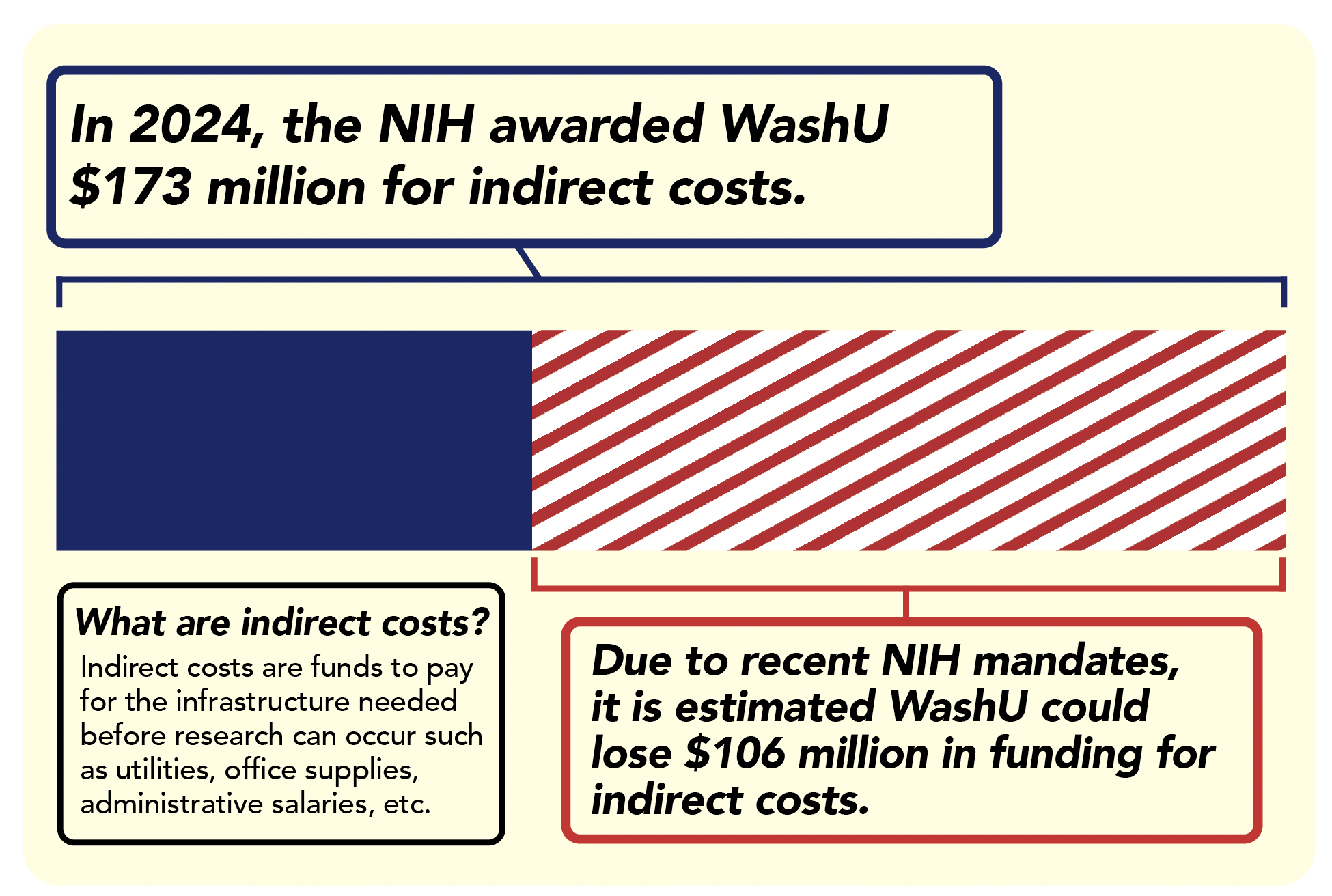

While the future of NIH funding is now uncertain, the cut to indirect cost reimbursement would have cost WashU about $106 million of research funding in 2024, according to Student Life’s analysis of the NIH funding database.

These “indirect” or “overhead” costs are defined as funds for facilities and administration. This includes infrastructure required for research that is not included in the direct grant, such as keeping the lights on, paying for employee benefits, etc. When announcing their decision, the NIH said accommodating these costs prevents taxpayer money from going towards direct funds for research.

Many in the scientific community have called the cut “devastating.” WashU, which is second in NIH funding, has similarly denounced the cut in an email statement made by Chancellor Andrew Martin this Saturday, which promised immediate action.

“These cuts also will be implemented by other federal agencies and stand to have a significant impact on institutions like WashU,” Martin wrote. “We’re mobilized on multiple fronts … to ensure that [government officials] understand the consequences of these cuts and are encouraged to act to address this threat to research and its many benefits to society.”

Researchers respond to cut

Research institutions typically negotiate their own indirect cost rate with the government every few years, depending on the type of funding. WashU, for instance, has negotiated a rate of 55.5%, meaning for every $100,000 granted for organized research from the NIH, the University would receive an additional $55,000 in indirect costs for research infrastructure.

However, these high negotiated rates, the likes of which NIH listed as a reason for the cut, can be misleading as universities often seem to receive less than their negotiated rate. WashU, for instance, has an actual average indirect cost rate of 38.5%, instead of the publicized 55.5%.

With the new guidelines, the NIH is setting the overhead rate at a flat 15%, meaning every institution in the nation would only receive an additional $15,000 per $100,000 for indirect costs. This change applies to all current and future grants, with the NIH stating they have the right to apply the policy to past grants but choose not to do so.

WashU has more than 1,000 NIH-funded projects underway at the medical school alone. The University received $731 million worth of grants from the NIH in the 2024 fiscal year alone, with around $173 million designated for indirect costs, according to Student Life calculations. If this policy had been in effect last year, the NIH’s change would have cut these funds to approximately $67 million.

A WashU professor who wished to be anonymous said members of their lab are “incredibly scared and terrified” by the prospect of an NIH budget cut. Another professor, who also wished to be anonymous, emphasized the distress the cuts have brought to their lab.

“Worry, frustration, and a feeling of powerlessness are the main emotions at all levels,” the second professor wrote in an email to Student Life. “With a cut of this magnitude, we would absolutely be expected to see major downgrades to research infrastructure like research facilities, equipment, and services across the institution that allow our lab to do what we do.”

A WashU professor, who wished to be anonymous and will be referred to as Professor Z, said this decision uproots the biomedical research pipeline.

“This is all a ludicrous proposition that fails to understand the whole ecosystem of how this all works,” Professor Z said.

“Indirects are the lifeblood of grants,” one professor who wished to remain anonymous and will be referred to as Professor Y, said. “Indirects are just so much more than just even the money. When you’re seeing those numbers, there are people behind them. It’s not just a light bulb. It’s actual people and their jobs.”

Professor Y does research that focuses on how to apply research innovations in beneficial ways for communities that need them. They have specialized in grant writing for about 20 years, and said that judging from their experience, people should be worried.

“The university is saying, ‘Don’t panic, we’re figuring this out,’” they said. “But the time to panic is now.”

To remediate the situation at an institutional level, WashU must either find new funding sources for this amount, reallocate current funds, or scale back research.

Associate Professor of Molecular Microbiology, Sebla Kutluay, said that while the University may be able to cut some indirect costs, the unaccounted costs will largely fall on the shoulders of scientists. To Kutluay, this cost could mean the end of research institutions altogether.

“Universities will not want to have scientists,” Kutluay said. “There will be no incentive for the universities to expand the science program [so] I think that will be the first thing they cut.”

A 2024 report from WashU’s School of Medicine stated that for every $1 million dollars in federal funding, 11 local jobs were created in St. Louis. In 2024, WashU received $731 million worth of funding, equivalent to the creation of 8,041 jobs according to the job conversion above. If the NIH cuts had been implemented last year, WashU would have received $100 million less in research funding, meaning 1,100 of those jobs would not exist.

Professor Z emphasized the value of NIH funding to the local economy.

“Every NIH dollar creates $2.70 in local income,” Professor Z said. “It pays itself back beyond the cures that could potentially come out of it.”

This may only be part of the jobs St. Louis could lose from the cut: local St. Louis research institutions are also facing financial pressure that can result in job loss.

Fimbrion Therapeutics, a biotechnology company developing alternatives to conventional tuberculosis antibiotics, had three grants that were affected by the NIH grant freeze earlier this month. Thomas Hannan, Chief Scientific Officer and Acting CEO of Fimbrion, and part-time research faculty at WashU, said there is still no timeline for their grants to be approved.

“The result is that it is likely that we may have to lay off half of our staff in the short-term until we have more clarity on future funding,” Hannan said.

Turing Medical, a St. Louis neuroimaging startup, wrote a statement to Student Life stating the cut would “significantly” affect their operations in St. Louis if it went through.

“For startups like ours, where every dollar is critical, even a small reduction in funding can lead to project delays or scaling back on ambitious initiatives,” Turing wrote. “It’s important to highlight that while NIH funding is often associated with large universities and well-established research institutions, it also plays a critical role in supporting small startups that are driving innovation.”

For Fimbrion, the NIH’s sudden budget cut was like “pouring salt on the wounds,” according to Acting Fimbrion CEO Hannan. He emphasized that the suddenness and lack of feedback solicitation from the NIH was “very atypical.”

“15% indirects is not sustainable for a small company like ours and shows a very poor understanding of how research works,” Hannan said. “To be honest, this is the worst three weeks of my professional life and morale is very low in our company, because these actions threaten our ability to carry out our mission and folks may lose their jobs.”

Associate Professor of Molecular Microbiology Kutluay said the NIH’s actions could also mean a large exodus of scientists from the United States in the near future.

“If you don’t have the opportunity, then people will move someplace else,” Kutluay said.

Professor Y is concerned that diminishing NIH funding will discourage the young generation from pursuing research for their careers.

“If they’re trying to stop people from writing grants, if they’re trying to stop people from not wanting to look at grants as a viable option for [their] career[s], then they’re succeeding,” Professor Y said.

Legal implications

Ever since the cut was announced, legislators and research groups alike questioned its legality, and Missouri legislators have not commented on the matter. But late this Monday, a federal judge in Massachusetts paused the implementation of the cut in the 22 states that filed a joint lawsuit, not including Missouri. The lawsuit states the cut is not legal on the basis that the directive did not go through Congress and will halt scientific advancement.

After the lawsuit from the attorney generals was filed, 12 universities and university-affiliated organizations filed their own suit, which caused the pause to become national. WashU is a member of the Association of American Universities and the American Council of Education, both of whom were part of the suit.

While the pause will alleviate the immediate threat to funding, questions still remain regarding the impacts on research funding and medicine over the next four years.

“[T]he real underlying concern here is that the current administration seems to have an anti-health agenda, […] which should alarm all Americans,” WashU Professor of Child Psychiatry Joan Luby wrote in an email to Student Life.

Professor Z anticipates more outrage to come regarding the budget cut, as a cut of this magnitude would likely impact medical advancement and, as a result, medical care in the US going forward.

“No place in the country is immune from health problems,” Professor Z said. “It doesn’t matter how you voted in the last election. It’s something that equally affects everybody.”

Vice Chancellor for Government & Community Relations J.D. Burton, Vice Chancellor for Medical Finance and Administration Richard Stanton, Vice Chancellor of Marketing and Communications Julie Flory, Dean of the School of Medicine David Perlmutter, Vice Chancellor of Research Mark Lowe, Dean of the School of Public Health Sandro Galea, and Professor of Law Jessica Sachs declined to comment.

Congressman Wesley Bell of Missouri’s 1st Congressional District also declined to comment.

How we did our calculations:

In the article, we stated that the indirect costs reimbursed to WashU by the NIH was about $173 million in 2024, and that WashU would have lost $106 million dollars if the NIH’s new policy of 15% indirect cost rate was applied to 2024. We approached calculating this from multiple angles.

We used the NIH’s database, which lists every grant given to an institution, including its date and direct/indirect cost reimbursement. We found that the sum of indirect costs for NIH’s 2024 fiscal year paid to WashU came out to be $188,746,897. With the new guidelines applied (multiplying the sum of direct costs by 0.15), this would have shrunk to $81,783,152, meaning a loss of $106,963,745 for the NIH 2024 fiscal year.

Notably, WashU has a different fiscal year than the NIH does, ending June 30 instead of Sept. 30. Recalculating using WashU’s 2024 fiscal year, the loss totals equaled $105,692,172. Because these numbers come straight from the NIH database for WashU’s 2024 fiscal year, this was the calculation used for this article.

Many other publications apply the institution’s negotiated rate to the amount of funds said institution received, dividing it by 1 plus the rate to give the direct cost amount. By multiplying the direct costs by the negotiated rate, then multiplying the direct costs by the new 15% rate, and subtracting, the loss of research funding as a result of the change can be found. This was the first thing we tried, by applying WashU’s stated rates to NIH’s list of funds given to WashU we calculated $259,024,350.59 of indirect cost for the 2024 fiscal year. If we apply the 15% rate instead, this would result in $71,008,871.01 of indirect costs, resulting in a $188,015,479.58 drop in research funding. However, in our opinion, this is the wrong answer.

Notably, based on our calculations in the article, there is a significant discrepancy between what WashU was promised by the federal government and what it actually received. That is where the difference between WashU’s negotiated 55.5% rate and actual average 38.5% rate originates. Our assumption is that many institutions tend to receive less than their negotiated rate, which is corroborated by a nature.com article which suggests that universities especially suffer from this.

Because of this unexpected conclusion, we tried to verify our numbers, but nobody in the administration that we emailed was willing to do so (or they did not respond). As one final check, we looked at WashU’s financial statement for 2024. Using some assumptions along with further calculations, we similarly got an approximate ~$106 million research funding lost for 2024 from using WashU’s own numbers. If you would like to learn more about how we did our calculations, email [email protected].