Movie Review

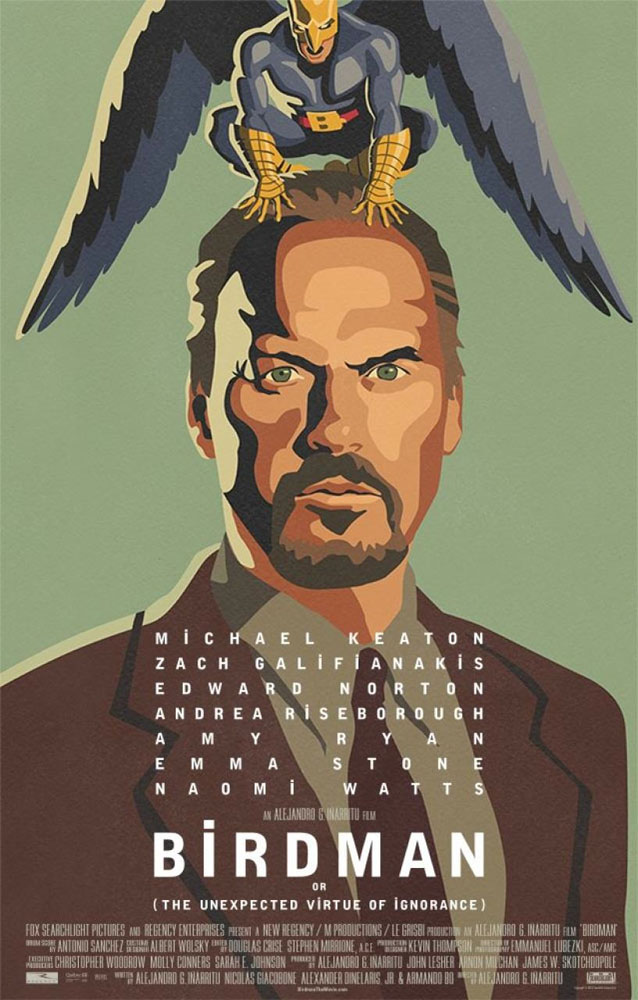

‘Birdman’ a wild but moving meditation on the artistic process

directed by Alejandro G. Inarritu

and starring Michael Keaton, Zach Galifianakis, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Naomi Watts, and Amy Ryan

So here’s the simple part. In “Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance),” Michael Keaton plays Riggan Thomson, an actor famous for playing the fictional superhero Birdman. Of course, Keaton himself is famous for playing, and abandoning, the role of Batman in Tim Burton’s incarnation of the hero.

Now, there’s a reason Michael Keaton was great as Batman. There’s a reason his portrayal is better than Christian Bale’s or Adam West’s or anyone else’s. Keaton can play crazy while maintaining a sense of great comedy and drama about his insanity. In Keaton’s Batman, suavity, courage and confidence were thin veils for whatever lay beneath, and it shows in “Birdman.”

From here, “Birdman” only gets more complex and downright fantastic. Riggan Thomson isn’t Bruce Wayne, but everything Keaton brought to Wayne is, especially the crazy. After several decades of wrestling with his ego, Thomson decides to write, direct and star in his own adaption of the Raymond Carver short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.”

As such, the movie takes place almost exclusively in and around the St. James Theater in New York City, where Thomson is preparing his adaptation along with preview performances and rehearsals. It’s a small, theatrical set that holds Thomson’s huge artistic hopes, and the film’s cinematography gives the audience this sense of claustrophobia. Long tracking shots and the incessant rhythm of drums carry us through the back hallways of the stage, forcing us to try and keep up with the actors. The colors of the stage drench the action in beautiful blues, greens and reds.

“Birdman” is the artistic vision of director/writer/producer Alejandro Inarritu (“Biutiful,” “Babel”). In a recent college conference interview, Inarritu described the film as an exploration of “the need [for] validation” and “the celebrity kind of disease that our society now has with the social media…approaching it with humor and laugh[ing] about it, because they are tragic, but at the same time they can be real fun.”

The film also satirizes the superhero genre, critics, and the split between stage and screen actors. Add to that a few romantic touches and knockout performances by a supporting cast including Emma Stone, Edward Norton, Zach Galifianakis and Naomi Watts, and “Birdman” becomes both an invigorating and fun movie.

Even from the first few seconds of the film, it is clear that Thomson has lost his grasp on reality. Floating in the air in his tighty-whiteys (a comedic costume fallback throughout), he is meditating and trying to get the haunting voice of his superhero part, Birdman, out of his head. It seems he can move objects with his mind. Or at least, in his mind he can.

The boundaries between fiction and fantasy are not incredibly clear in this movie, and that’s the fun of it all. As Thomson, Keaton is hilarious and disturbing, incredibly grounded and yet fantastical.

The entire ensemble takes part in the brilliant, dark comedy born out of misery and denied ego. Keaton and Norton (who plays the brilliant but damaging stage actor Mike Shiner) spar beautifully in their scenes together, both verbally and physically. One of the comedic highpoints of the film features the two rolling around, fighting each other on the floor.

Zach Galifianakis gets his laughs in, too, playing the uptight, showbiz-type producer and Thomson’s best friend. Galifianakis’ character yells most of his dialogue out of the sheer frustration of working with the people around him. Naomi Watts plays Lesley, the straight man to Keaton and Norton’s comic foils. She expertly throws out dry, witty lines despite her character’s floundering romances.

Meanwhile, Thomson’s daughter, played by Emma Stone, copes with the aftermath of rehab by smoking weed, yelling at her dad and making thousands of tiny marks on a roll of toilet paper. It’s funny, but maybe not always laugh-out-loud funny.

In describing the inner world of Thomson’s play, Inarritu said, “The wrong choices were made deliberately to obviously show how wrong everything will be going.” True to form, the whole play is constantly in a state of falling apart and being put back together. Thomson falls apart too, leading to a psychological breakdown and an interlude wherein he allows the Birdman-side of his consciousness to take over. This leads to scenes filled with giant robotic birds, human flight and other superhero tropes.

These tableaus are fantastical and can feel out of place, but Inarritu builds up to them carefully enough that he earns the spectacle. Everything culminates in the catharsis of Thomson’s play’s opening night performance. The stakes are high, the characters are bruised and broken and the conclusion is hilarious, surprising and ultimately ironic.

In all the comedy, metafiction and spectacle of “Birdman,” it is clear who is in control. Inarritu puts every piece together with care. He has described the journey to the film’s completion as a parallel to Thomson’s play. Inarritu doesn’t do it all alone, though.

“Birdman” comes from the strong partnership between Inarritu and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki. These two have worked together for quite a while, and it shows in the smoothness and blocking of the long takes that populate the film. At its center, “Birdman” is Inarritu’s meditation on the creative process and what drives artists to bring something into the world. Despite all the pain it may bring, Inarritu’s process has yielded a film that is thoroughly funny and artistically compelling.

“Birdman” opens in St. Louis on Thursday, Oct. 23 at both the Plaza Frontenac and Tivoli theaters, with showings at 8 p.m.